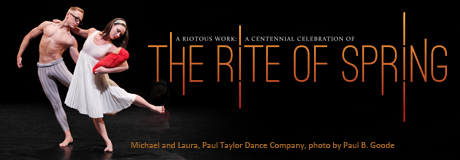

The Rite of Spring is the theme behind one of the latest exhibits at the National Museum of Dance – here’s a closer look, courtesy of Sarah Hall Weaver, the Assistant Director there…

Can you talk a bit about how the exhibit “A Riotous Work” came about?

I’ll give you the short story…we actually had another exhibit planned that fell through leaving us in a bit of a bind about a year ago. The Rite of Spring has always been one of my favorite historical dance topics and I have had it in the back of my head for years as a potential exhibit concept. While sorting through our options we realized the centennial anniversary was quickly approaching and that eliminated all debate – something had to be done to celebrate this momentous occasion. The original work had such a tremendous impact on the course of dance and music history, it is something dance lovers young and old should have some awareness of.

For those who are not familiar with this ballet, can you explain its significance?

Haha…oh no…ok…short version here too…

This ballet premiered on May 29, 1913 in Paris. It was choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky [imagine the Nureyev or Baryshnikov of their time], the music was written by Igor Stravinsky [this guy created DOZENS of ballet scores, many of which you probably know and know well], and it was performed by the avant-garde ballet company the Ballet Russes.

To fully understand the significance you have to put yourself in that time – there are no TV’s, no computers, the ballet and orchestra were coveted forms of entertainment, and the audience was used to the fairy princesses and sparkling tutus that we still often associate with ballet today [remember modern dance is just igniting at this very same time]. They were also used to the music that went along with it. Stravinsky and Nijinsky created a ballet that was set in pagan Russia – a chaotic world relatively unknown to Western European audiences.

The story is of a sacrificial virgin that is offered up to ancient gods so that spring will return once again. The choreography was flat footed, turned in, and abstract; it eliminated all of the prestigious pointe work and tricks that defined ballet up to this point, and oh boy – the music! The music used pounding, repetitive, abrasive beats that were unheard of in 1913. Stravinsky abandoned charming, hum-able melody, and put all attention on crashing rhythms. The audience went bananas.

There are many first-hand accounts of that night and they all describe immediate outbursts at the first sounds of the music, people standing up from their seats and screaming at the stage and at each other, audience members slapping other people in the next row – can you imagine getting slapped at the ballet?! The audience uproar alone was unlike any other. The Rite of Spring was only performed a few more times and was then lost to history. Since then though the music has been used by dozens of choreographers and companies. It has be reapplied to modern concepts and researchers have even resurrected a close variation of Nijinsky’s original choreography – that alone is a unique aspect of this work, few if any other ballets have been dug up to this degree. In all…it changed what ballet could be, it opened the doors for completely new approaches to choreography in all forms of dance, and it kept ballet relevant to the rapidly shifting arts and social movements of the twentieth century.

Many dance organizations are celebrating Rite of Spring this year – what makes this particular exhibit stand out?

We actually reached out and spoke with a few different groups as we began planning our project – it really is exciting to be a part of a worldwide celebration, and no one organization is doing the same thing as another. We are not offering live performances like many companies and other arts organizations, this exhibit is almost designed to catch you up if you aren’t on board already. We wanted to give our audiences a good understanding of the original work and how it has survived through history. We selected a small group of other companies and choreographers to exhibit profiles on – how their works were different or similar from Nijinsky’s and each other’s. I really stand by this work as a necessity of basic dance history education and that’s how we looked at our exhibit – a resource to understand this piece from its very beginnings to the new productions that are being produced today and that are promised for tomorrow.

How did you select the items that would be on display for this exhibit?

We worked individually with each company featured in the exhibit and discussed with them what was available from their collections while we also pulled several items from our own archives. A lot of companies are using their costumes this year so unfortunately we couldn’t include many of those [in the long run we’d rather they be on stage than in our cases anyways ;-)]. Several companies also suffered great losses from Hurricane Sandy – a lot of the retired costumes that may have been contributed otherwise were destroyed or are being salvaged as we speak. That was a very sad component of our conversations but hopefully with continued support they will be able to recover their collections. I ended up including some interesting objects like a 1932 record set of the music conducted by Stravinsky himself. It is a beautiful album with a textile cover and gold lettering – in the time between 1913 and 1932 the music clearly went from being an outrage to a masterpiece!

What was your favorite part in terms of pulling this exhibit together for the museum?

I loved becoming more familiar with the later variations of the Rite of Spring – it’s so interesting to compare and contrast each choreographer’s take on this piece. It almost reveals the essence of each artist. While researching I kept finding more and more variations, all over the world, in all styles of dance, and from every decade between the original premiere and today. There is a special sensation about the music of the Rite of Spring and about its dance legacy that draws in so many of our greatest artists…there is always more to learn and more to see. The same goes for the original work – every source your find leads to another, there are a lot of accounts and a lot of opinions of why this work was so important from the start. It was easy to get swept away.