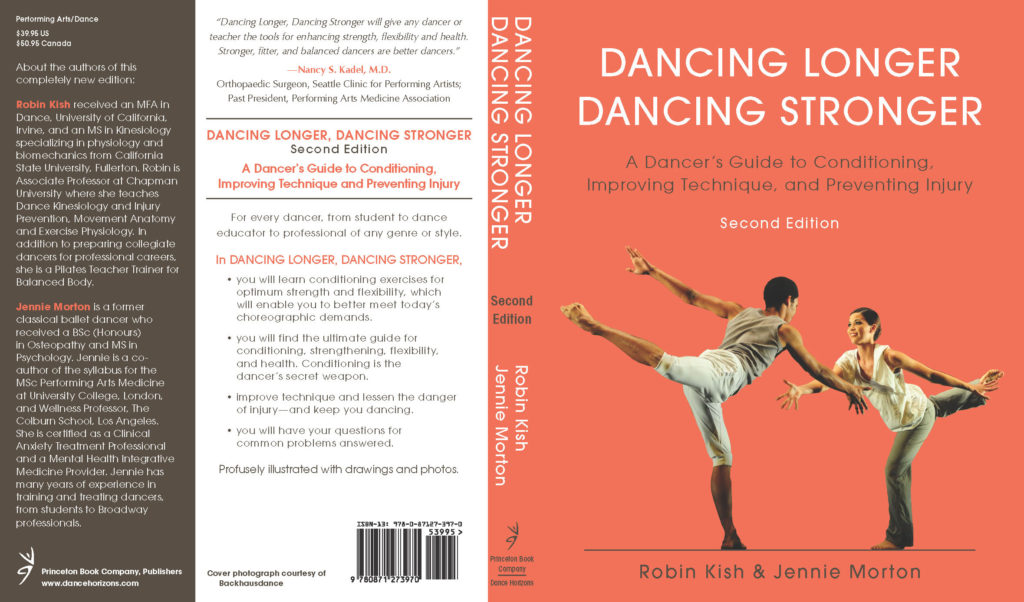

I’m very pleased to be able to let you know about a new dance medicine book just published by Princeton Books, Princeton, NJ. This is a 2nd edition of one of the classics of dancer medicine literature — “Dancing Longer, Dancing Stronger“, originally written by Priscilla Clarkson and Andrea Watkins, published by Princeton Books in 1990. This new, updated version has been written by two IADMS (International Association for Dance Medicine and Science) colleagues of mine, Robin Kish, MFA, who has written previous articles for 4dancers.org, and Jennie Morten, BS, MS. This resource is again published by Princeton Books, in Princeton, NJ.

Robin has a strong background in physiology and biomechanics, and is currently Associate Professor of Dance at Chapman University in CA, where she teaches Dance Kinesiology, Injury Prevention, Movement Anatomy, and Exercise Physiology and Conditioning. Jennie is a classically trained ballet dancer, with degrees in Osteopathy and Psychology, and is lecturer at the University College, London – Division of Surgery and Interventional Science, and also wellness professor at the Colburn School, Los Angeles, CA.

The original DLDS was one of the early (and comprehensive) books about conditioning / avoiding injury written for dancers, and was an invaluable aid for dancers and teachers over many years. Robin and Jennie have done an excellent job in updating the information and adding new segments to the book. It is full of specific conditioning exercises, and is something dancers should carry in their dance bag or have on their devices, for quick reference. This is a must have for every dancer / teacher – I encourage you to bring it into your dance library.

Below is a brief segment from the new book, on the importance of cardiovascular fitness for dancers — an important ingredient in lowering one’s injury rate, and something we often forget. Enjoy, and Pass It On!

– Jan Dunn, Dance Wellness Editor

Cardiovascular Fitness (Princeton Book Company, Publishers, © 2019, excerpt below courtesy of the publisher)

Research has shown that although dancers perform slightly better than non- dancers in terms of their cardiovascular fitness, they lag significantly behind other athletes (Rodrigues-Krause, Krause, and Reischak-Oliveira 2015). Dance classes typically have a stop/start nature involving short exercises with rests in between. This primarily works the body anaerobically and trains it for short bursts of activity—the equivalent of being a short-distance sprinter. However, the choreographic demands of performance often require dancers to sustain activity for 15 to 20 minutes, or perhaps even longer. This requires aerobic fitness—the equivalent of being an endurance athlete. If this is not being trained during a dance class, then it is essential to have a supplemental training routine that pro- vides aerobic training. Fatigue is a significant risk factor for injury. Therefore, having a cardiovascular system that can meet both the aerobic and anaerobic requirements of a dance career means that you will have improved endurance, will not tire as easily, and will have a reduced risk of injury. Cardiovascular fitness also plays an important role in injury recovery—the fitter you are, the quicker you will heal.

To improve your aerobic fitness capacity, it is recommended that you undertake exercise that elevates your heart rate to 70–90 percent (depending on your fitness levels) of its maximal capacity for 20–30 minutes, 2 to 3 times a week (Wyon 2005). To calculate your maximal heart rate (MHR), you use the simple equation of 220 beats per minute (bpm) minus your age. Then calculate 70 percent of this to find your target heart rate (THR) for starting these exer- cises. Here is an example for an 18-year-old dancer:

220 – 18 = 202 bpm (MHR)

202 x 0.70 = 141 bpm (THR)—70 percent of your MHR 202 x 0.90 = 182 bpm (THR)—90 percent of your MHR

You may want to start your aerobic training program at the 70 percent end of the range, so for the first week, work at a heart rate of 141 bpm; then the next week, move up to 75 percent and so on until you reach the 90 percent mark.

There are many options you can choose for your aerobic training. These include a static exercise bike, elliptical machine, swimming, skipping, or running on a treadmill. You may want to take into consideration the impact on your joints of some of these activities. For instance, you may wish to choose cycling, elliptical machine, or swimming to avoid loading the joints of the feet, knees, and spine. You can measure your heart rate using a fitness-tracker watch or by using one of the free heart-rate apps available for smartphones. Additionally, some exercise equipment in gyms, such as static bikes and elliptical machines, have built-in heart-rate monitors on the handlebars.

While supplemental cardiovascular training is recommended, it is also considered good practice to include some dance-specific endurance training into dance class itself. Teachers could design this into the class perhaps once a week so that the dancers only need to undertake supplemental training another two times outside of class. This could involve either a high intensity warm-up that is continuous over 20–30 minutes or a center combination that is learned incrementally, then performed for the purpose of continuous repetition over a similar time period (Rafferty 2010). In this way, the endurance requirements for a dancer’s fitness can be addressed within the artistic environment of a dance setting, and not just relegated to a supplemental training routine in a more athletic environment.

About the authors of this completely new edition: Robin Kish received an MFA in Dance from the University of California, Irvine, and an MS in Kinesiology specializing in physiology and biomechanics from California State University, Fullerton. Robin is Associate Professor at Chapman University where she teaches Dance Kinesiology and Injury Prevention, Movement Anatomy, and Exercise Physiology and Conditioning. Jennie Morton is a classically-trained ballet dancer who received a BS with Honors in Osteopathy and MS in Psychology. She is a lecturer at the University College, London, Division of Surgery and Interventional Science, and wellness professor, the Colburn School. She is certified as a Clinical Anxiety Treatment professional and a Mental Health Integrative Medicine provider. Jennie has many years of experience in training and treating dancers, from students to Broadway professionals.