Early 20th Century Dancer Florence Fleming Noyes Takes a Somatic Approach

by Nancy Wozny

I took the idea of staying home to include the home of my body, and the home of my dance life, which is based in Somatics.

Somatics, defined by Thomas Hanna in the 1970s, translates to an experience of the body from within, and is now an umbrella for an ever growing cluster of disciplines including: the Feldenkrais Method, Alexander Technique, Body-Mind Centering, Continuum Movement, The Franklin Method, and many more. Although we think of somatics as concerned with our inner sensations, it also emcompasses body mechanics, alignment, learning to be a more easeful mover, slowing down, and feeling more.

During my pandemic adventures into the soma-sphere I moved in both directions in time, from studying with the new crop of dancing Feldenkrais teachers to exploring vintage somatic methods, such as Noyes Rhythm, a method, that chances are, you’ve never heard of.

Relax, a few months back, I was right there with you.

It was at a performance of Celebrating Isadora Duncan with Lori Belilove and Sara Mearns at Virtual Jacob’s Pillow Festival on May 27 that reconnected me to my friend Meg Brooker, who had left Texas to become an Associate Professor at Middle Tennessee State University.

I had some questions for Brooker about the Duncan technique after the show. She answered them in a generous email, and also invited me to her Duncan and Noyes Rhythm classes.

I joined both classes. We are well acquainted with Isadora Duncan, as she was generously historicized by scholars and Hollywood. As for Noyes Rhythm founder, Florence Fleming Noyes, not so much; perhaps, not at all. I joined the Noyes Rhythm “recreation” class via Zoom knowing next to nothing.

Within days, I was soaring about in my cramped apartment, inspired by Brooker’s narrative of cloud formation, wistful breezes, unfurling leaves, and other elements of growth and shift in the natural world.

I needed to know more.

Brooker also sent me her writings on Noyes (1871–1928), a leading figure in the free dance movement, often mistaken as a Duncan imitator. She describes Noyes Rhythm as “an early twentieth century somatic practice through which dancers increase the depth of their capacities for experiencing free, joyful, and expressive movement.”

As someone deeply invested in the entire continuum of body-mind based practices, the word “somatic” caught my eye.

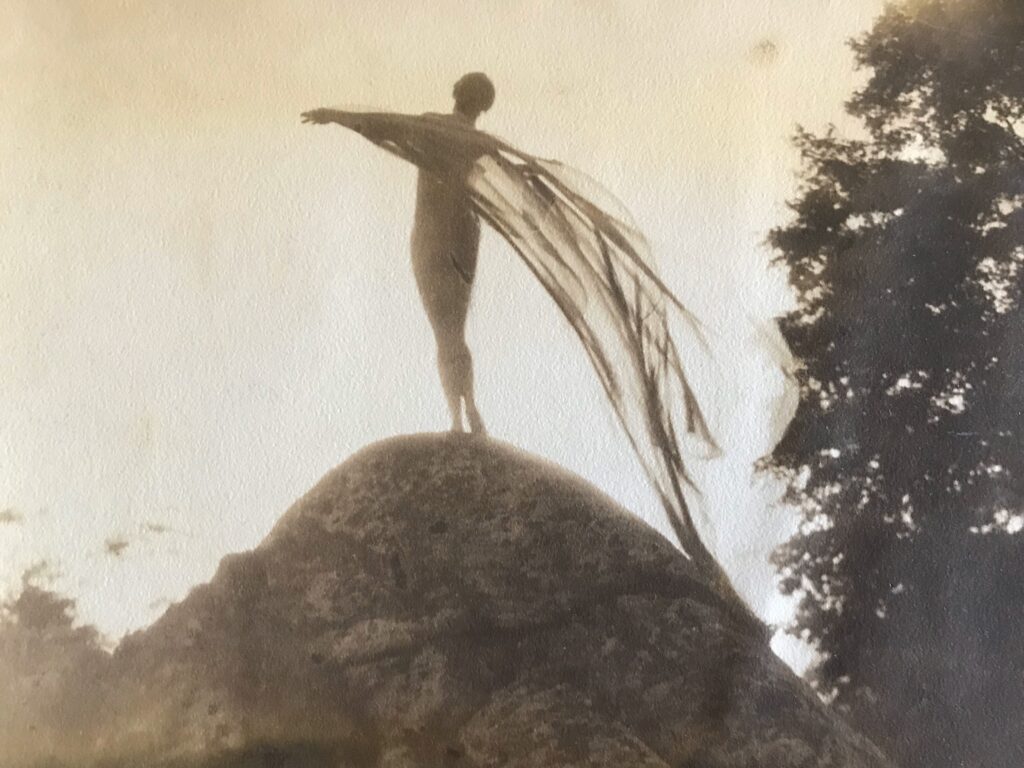

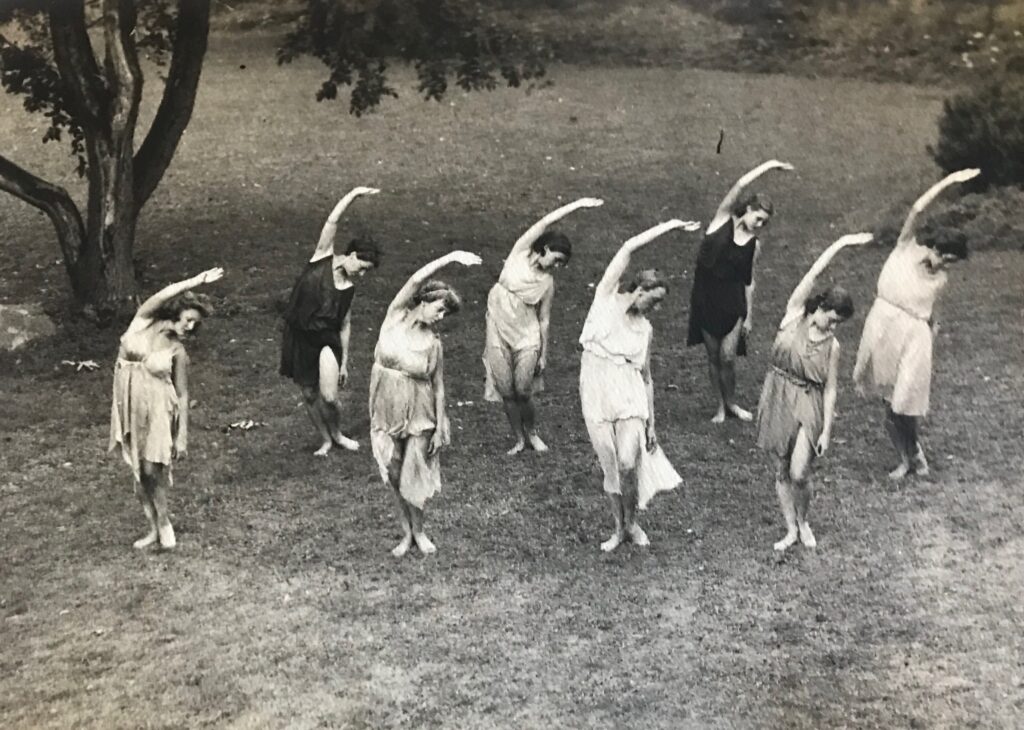

Quite the entrepreneur, Noyes founded the Noyes School of Rhythm in 1912 at Carnegie Hall, with branches in major cities throughout the U.S. In 1919, she settled at Shepherd’s Nine in Portland, Connecticut, where one can still today learn, study and explore on the glorious outdoor dance studio.

Brooker, now one of 12 Noyes Rhythm teachers, is bringing this body of work out of its seclusion at Shepherd’s Nine and into her studio at Middle Tennessee University, along with workshops for dance educators and classes for the public.

Noyes, a frequent performer during the Suffrage movement, was brought back into our vision when Brooker recently re-constructed and reconceived Noyes’ Dance of Freedom on her students in honor of the anniversary of the 19th Amendment.

Noyes Rhythm involves two movement experiences: the technique class, and the recreational class, and each of those have their unique structure. Both reveal strong somatic values.

Brooker has served on the Noyes School of Rhythm Foundation Board of Directors, and is currently the Archive Director. She has presented workshops on Noyes for the Dance Studies Association, Society of Dance History Scholars, Congress on Research in Dance, and the Isadora Duncan International Symposium. In addition, she is also a legacy Isadora Duncan dance artist with an international performance background and holds an MFA in Performance as Public Practice from UT Austin and a BA in Theatre Studies from Yale.

I visited with Brooker to get a clearer idea of how Noyes fits into the ever-growing somatics canon.

Nancy Wozny: I see somatics as a porous and expansive field, open to new information, even if that information is, well, old! Noyes used the term, “sentiency,” which is much more poetic. What exactly did she mean?

Meg Brooker: When we talk about sentiency in Noyes Rhythm, we are talking about a feeling of aliveness, of interconnectedness, it is innate embodied knowledge.

NW: Aliveness is a close cousin to awareness. Interconnectedness lies at the root of many body/mind based practices, especially in considering how every movement is a movement of our whole body. Are you also talking about the human body in relation to the natural world?

MB: Yes. In Noyes, we study movement and growth in nature. There is a deep intuition and a sense of following, allowing, creating space for unfoldment to happen. We go into the body and follow the body’s movement impulses, and we do it in a playful and joyful way.

NW: Joy doesn’t get talked about enough in somatics! But how does sensing manifest in the work?

MB: We use the term “feel” a lot in our teaching. Feel the moss underneath your feet. Feel the warm sun on your back. (And we teach this work in the summertime outdoors where you really can walk barefooted on moss and stand in the warm sun). There is a huge emphasis on releasing tension, on relaxation and playfulness. The “letting go” of thinking, of mental activity, so that the body is leading and the mind is following. Sentiency is a kinesthetic awareness.

NW: I am so glad that we are talking about moving outside, because I’ve done quite a bit of that this past year. It is awakening to be moving while feeling and hearing a breeze, and other textures in our environment. Being in the natural world gives us something to attend to along with our bodies.

MB: We also talk about the “elemental,” meaning feeling the elements. Being outside in nature is important for understanding this– this is an exploration that challenges what is comfortable–mud, cold rain, strong winds are examples of elemental feeling.

NW: Noyes’s former student Valeria Ladd writes in her 1949 book, Rhythm and the Noyes Technique, “It is desirable that the dancer be unconscious of the body as a body; either a heavy body or a light body, it will always be in the way if it is in the thought of the dancer.”

Two things jump out here in terms of somatic thinking: First, it rarely helps to think of a body as an object, which so often happens when we use mirrors. Second, the notion of getting out of your own way is embedded in so many disciplines. There is an underlying premise in somatic methods that we are not so much doing as undoing. Tells us more about how these ideas manifest in Noyes’s work.

MB: In Noyes Rhythm, we are “dropping off the head”– literally! Similar to Duncan technique, we focus on the solar plexus as a center of movement initiation and of coordination, and in Noyes Rhythm we call this high center “the spot.” One thing I often tell students is that while much of their dance training is taught from the musculoskeletal system, these early modern practices prioritized coordination of the nervous system.

NW: Wait, what? Noyes was aware of the operation of the nervous system and its role in sensing movement? Well then, she was way ahead of her time. Say more.

MB: We “follow” the movement in a sequential way, “feeling” the patterning from the nervous system, so there is awareness of movement and sensation through the whole movement pathway, not only at the joints.

NW: So she was aware of the kinetic chain of motion. Impressive!

MB: Yes, she used terms like: letting go, dropping off, allowing, following, not doing.

NW: Juicy words for a somatic denizen. It seems like Noyes had her own hierarchy when it comes to the mechanics of the body though.

MB: Noyes identified the vertical axis, the line over gravity, as the “axis of being” and the horizontal axis, the line underneath the arms when stretched out to the sides, as the “axis of doing.” There is emphasis in the technique of “dropping off” the arms, as well as the head, so that the high center of the body is leading. The arms can get swept up in movement, but they are secondary. Noyes trains dancers to let go of “willful” movement.

We work on breaking and disrupting habitual patterning.

NW: Boom! Noyes Rhythm earns its somatic stripes with that statement. That’s great, but exploration is integral to many somatic disciplines. Is there leeway to find one’s own way?

MB: Yes! The Noyes techniques have both a “physics simile” and a “symbol.” The physics simile is the rote mechanics of the movement, what she might also call mathematics. For students new to the work, it is important to learn these basic patterns or movement pathways.

The symbol is what animates or enlivens the movement pattern. Noyes Rhythm is taught through the symbols or images. This pedagogy encourages newness, freshness. I’m thinking of something an old acting teacher used to say, which is “always for the first time.” There is an aspect of spontaneity and newness that is very important, and the movement is in response to the image.

NW: I want to get to Noyes’s use of images, but first we have to address novelty, a major component of many modalities, including my somatic home, The Feldenkrais Method. Precisely guided exploration is how we find fresh pathways. Can you give us an example of how this manifests in the Noyes work?

MB: Yes, one of my favorite techniques is the spot and radii floor stretch. In this technique, the dancer begins lying on the floor in a long line, with the legs together and the arms outstretched overhead as if the body was the diameter of a circle. The mechanics of the movement are for one arm and leg (the limbs in this exercise are the radii (limbs are also called trailers) to trace an arc towards each other on the floor, and then back to the center line. The “rhythm passes” and is picked up on the other side.

This technique is often taught with the image of a single raindrop plopping into a still pond, and sending arcs of waves widening out toward the shore. The raindrop is felt right at the spot, and, as radii, the arm and leg are imaged as connecting to this spot. The force or weight of the raindrop is the cause and the long arm and leg are released into the arcing pathway as a result of this felt impulse.

Each time this movement happens, it is a new raindrop with a different mass, different force, different momentum. Because the limbs are moving in response to this image impulse, the degree of movement will vary. How far the limbs move is not what is important, feeling the coordination from the image impulse through the movement is key.

NW: I am glad to hear that it doesn’t matter how far the limbs move. Quality over quantity is important here. Since you brought up the raindrop image, let’s move in that direction now. I have recently returned to the work of Mabel Todd, Lulu Swiegard, André Bernard, Eric Franklin, and others who have used imagery in their work. Nature images are central to Noyes. Help us understand her use of imagery.

MB: The vegetation stretch can be helpful to dancers, and it is basically the pattern of a grande ronde de jambe with the image of seaweed stretched out and floating in the waves.

In Noyes technique, the pattern starts with a basic leg fold, in which the dancer softens at the base of the sternum (the “spot” drops) and gently folds at the hip, knee, and ankle of the standing leg, allowing the other leg to release to the front, and then drawing the released leg into a tight fold with flexion at the hip, knee, and ankle and a C-curve in the spine. The sternum lifts (“spot” rises), as both legs lengthen, the standing leg rooted into the earth as the released leg extends away from the center and floats–like a length of outstretched seaweed–around from front to back. The outstretched limb lowers down as the spot drops and that leg takes the weight as the rhythm passes to the other side.

NW: Ah! Seaweed is a marvelous image for motion, but let’s keep this somatic inquiry going. Rest is present in most somatic disciplines and serves multiple functions. We can sense differences, and we can let the work do its work in our neuromuscular organization. How might we experience rest in a Noyes class?

MB: Rests exist in many aspects of Noyes. One difference between Noyes and how other somatic disciplines incorporate rest is that we are not directing the mind to notice the effect of the rest. We are not directing the mind at all. We are cultivating deep embodied awareness and staying in that space, building an endurance for sustained awareness.

NW: So there is an ebb and flow of doing and not doing.

MB: Yes. The Noyes work historically was a “rhythmic” movement practice. Most of the technique exercises have active and passive moments–one side of the body is engaged, lengthening and the other side is resting, passive, and then the “rhythm” transfers and activities the passive parts, allowing the active parts to rest.

NW: Explain how rest is built into the improvisation class structure.

MB: Noyes Rhythm classes have three parts, and each section of the class is separated by a deep rest. Imagine going to a yoga class with two savasanas during the class!

NW: Sign me up!

MB: The first part of the “recreation” (or improvisation) class is a warm up with playful, whole-body movement. In this section of class we shake off, drop off the “personal,” let go of self-consciousness (this was huge for Noyes) and this part of class usually involves connecting to breath, opening the body, and may also include some locomotive and aerobic movement. Imagery may have a deep elemental feeling–rainstorm, volcanic eruption, change of seasons. In the deep rest, there may be imagery of disintegration, dissolving, further letting go, or of being held, safely rocked in the earth. There is music, and the quality of music will also guide the rest. It is a time for un-doing and for doing nothing.

NW: Efficient movement is a common thread in somatic practices. We are often looking for the “just enough” effort when doing any movement, activated muscles as needed to avoid overdoing. Where does Noyes stand on that concept?

MB: Noyes Rhythm absolutely trains efficient movement patterns. Noyes was vigilant about correcting over-efforting in her students. She identified over-efforting with “willfulness.” For Noyes, “willful” movement is straining, recruiting too much muscular force to accomplish an action, and misunderstanding the difference between strength and tension. Her pedagogy emphasizes balanced action. There is nothing rote, mechanical, or externally motivated in the Noyes work.

Noyes also talks about overflow or the 110%. This idea is that there is a letting go, and emptying out that happens (in other practices this is talked about as yielding), and then a filling back up–the movement doesn’t happen until there is overflow–until you have been filled up to 100%, fully enlivened, fully aware, saturated with sentiency, and then the extra 10% is the movement.

NW: It’s in this language that it reminds me that we are looking at a different time in history, and ways of being in our bodies.

MB: Yes, these early moderns, both Duncan and Noyes, were also interested in the relationship between the body and light. Duncan talked about “luminosity of the flesh” and Noyes also talks about an effortless feeling in movement, a feeling of the body disappearing and being moved by the music, what she also calls “leaking over gravity.” If we think about the relationship between light and energy, light and force, and also energy and matter, then this sensation of the body as light seems to result from finding the perfect balance between effort and action to create movement.

NW: I have no idea what leaking over gravity is, but it sounds splendid. I love the idea of emptying and refilling. Sometimes I feel that the dance field is just heading in a “more and more” direction, as in harder, higher, and more extreme.

MB: I know what you mean! I see this tendency to push the body to extremes in my undergraduate dance students. They are so focused on end-gaming the movement, on finding the most extreme form of a shape, and often doing this through over-efforting (they are wonderfully dedicated hard-workers). I incorporate Noyes Rhythm into my teaching of undergraduate dancers. It is a revelation to them to find, to feel, just the right amount of effort for the movement to happen, and to feel the joy and satisfaction of moving with connection through a small range of motion, as well as through a larger range.

NW: Thanks for the segue! I do want to know more about how you bring this work into teaching right now. How do you frame it to have value for today’s students?

MB: This work has so much value for today’s students–from both a general wellness and mental health perspective as well as from a dance technique training perspective. It teaches the importance of deep rest. It teaches the value and simplicity of just being (not always doing). It offers space to experience a huge range of qualities of movement and expression. It enables students to find and feel dynamic alignment and balance and to cultivate integrated, whole-body strength. It also cultivates a space for fun and play! Noyes Rhythm reminds us that the joy of moving is an experience that is always there, always available to us as dancers. It is an empowering and important reminder.

Nancy Wozny is editor in chief of Arts + Culture Texas, reviews editor at Dance Source Houston and a contributor to Pointe Magazine, Dance Teacher and Dance Magazine, where she is also an contributing editor. She has taught and written about Feldenkrais and somatics in dance for two decades.