by Allan Greene

Bach: Antipathy, Sympathy, Neuropathy

I recently was hired to play some classes at the Juilliard School. Even though I’ve been playing for dancers in New York City on and off for the last 34 years, I hadn’t really worked at Juilliard since my early days, the winter of 1980, when I was taken aboard to play Janet Soares’ dance composition classes.

Since the 2006-2009 expansion and renovation, Juilliard the physical plant has shed its insular, monastic feel and opened out to the world. It’s become a contemporary palace with a continuous view of its fiefdom, the collective components of Lincoln Center. Where in the past all you could see from inside was a bit of daylight from clerestory windows in each of the perimeter studios you now see the city and all its bustling creativity. This is important, because historically the inwardly-focused Juilliard (music) community had, intellectually and psychologically, largely lost touch with the world around it.

Back in 1980, I was exposed to the predominant choreography pedagogy of the time, which had sprung from Louis Horst, a dance accompanist, long-time companion of Martha Graham, and, for many decades, teacher of how to make dances at Juilliard. Mr. Horst taught that one could compose dances the same as one composes music, as an abstract language made of gestures manipulated in musical periods of time.

The style of musical composition that Mr. Horst’s approach most closely approximated was that of the Baroque contrapuntal masters, above all, Johann Sebastian Bach. This led to a lot of modern choreography set to imitative counterpoint, much of it very good. Horst had certainly discovered something.

As the accompanist to many of the new dances, I had to come up with a lot of Baroque material. Frequently, the length of the dances did not fit with any particular piece, and I had to improvise. I got pretty good at improvising in most Baroque forms, and especially in three- and four-part fugues. I never really thought that much about it, because I just sat down and did it. No big deal. Baroque music wasn’t all that interesting to me, and most of Bach’s music I found emotionally stunted. I really didn’t get what so many others seemed to get out of it.

A couple years ago, I was working with Alexandre Proia, the great New York City Ballet dancer and now teacher and choreographer. He had asked me to play from Bach’s Goldberg Variations so he could create material for a class. The exercise and the class went quite well, and afterward Mr. Proia was waxing eloquent about how wonderful Bach was. I confessed to him my feelings about Bach, and he gave me that “I can’t believe it” reaction I had seen so many times from Bach fans.

I decided then and there that I was going to find out what it was I wasn’t getting. I read a book of pop musicology about the Six Unaccompanied Cello Suites (The Cello Suites: J. S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque Masterpiece by Eric Siblin). I bought a big book (Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician) by the pre-eminent contemporary Bach scholar, Christoff Wolff, and read it slowly from cover to cover. I listened to many works he praised that I didn’t know or found uninteresting in the past. I started going over the Well-Tempered Clavier again, after ignoring it for three decades. I devoured a book written about the political and cultural context in which Bach composed his Musical Offering (An Evening in the Palace of Reason: Bach Meets Frederick the Great in the Age of Enlightenment by James R. Gaines). One anecdote in the Musical Offering book that stuck in my mind was this. Bach was apparently so adept at composing fugues that he could look at a few notes and plan in his head how the entire piece would turn out, in such detail that he could say at what measure what particular event would have to happen.

Bach wrote an astounding amount of music, made the more so because he had some pretty demanding day jobs (married twice, father of twenty children, Kapellmeister for a number of Thuringian courts, head of the music school at the Church of St. Thomas in Leipzig, regional publisher and distributor of his and other composer’s works, consultant on organ construction and repair). Hundreds of fugues poured out of him.

Constructing a fugue is not for amateurs. It has many working parts that simply must fit together, and the way the parts fit is dictated by the mathematics of the fugue melody and different for each fugue. I consider myself a pretty good fugue improviser, but to write fugues with the variety and perfection of form that Bach did is on another level altogether. Bach, I have come to believe, must have had something wrong with him.

The Neural Architecture of Creativity

I got interested in Bach’s brain. I knew a little about current models of how the brain works, and I thought I might be able to gain some insight into how Bach’s worked.

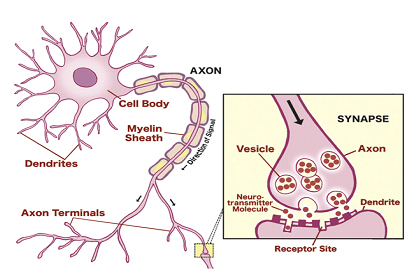

The human brain is rife with nerve cells, called neurons. A recent (2009) study calculated the possible average number of neurons in the human brain at 86 billion. The neurons are linked by pathways called axons, each of which ends in a little bundle called a synapse. The synapse at the end of the axon is an incredibly tiny distance from another synapse, connected to another axon and another neuron. Small amounts of electrical current pass through the neuron network by jumping across the gap from synapse to synapse. The network among the 86 billion neurons is, in the normal brain, complete, like a highway system with no dead ends (although plenty of lightly-traveled right-of-ways).

The modern science of neurology started in the years after the Civil War. The use of firearms resulted in numerous skull injuries, and there were many survivors who sustained less severe physical damage. Doctors observed that some of the wounded who had lost pieces of their brains were impacted in specific functions, and began mapping the affected areas of the brain. In the early years of the twentieth century, Korbinian Brodmann mapped the brain based on the locations of different kinds of cell structures, and correlated these areas to differing functions (hearing, body sensation, emotion, taste, memory, motor and vision). There are fifty-one of these “Brodmann areas”.

What’s interesting to me is how the neural network passes in and out of the Brodmann areas, enabling differing brain functions to “light up” in an infinite variety of sequences. This enables us to have complex thoughts and perceptions. (Allow me to be enormously simplistic for the sake of clarity.) Just as there is an infinite variety of individuals all called human beings, there is an infinite variety of ways that the neural system can grow inside the brain. From before birth, the neural system is growing. Neurons are connecting to other neurons in all sorts of sequences, in all sorts of areas. The neurons of the part of the brain that allow us to understand words develops prior to the area that enables us to speak words, and only after more than a year outside the womb do the neurons of the infant reach each other from both areas so that speech and understanding language can begin.

Now we can begin to talk about synesthesia. Synesthesia is a phenomenon that was first noted by Darwin’s cousin Sir Francis Galton, but until recently not been the subject of serious study. Synesthesia is the experiencing of two linked senses simultaneously and habitually. As an example (of grapheme→color synesthesia) there are many people who see numerals as specific colors, 7 as purple, 5 as a rust color, 2 as a throbbing white (I’m just assigning random values here, because each synesthete’s palette is different). There are people who hear specific tonalities (not pitches, but tonalities) as specific colors (known as sound→color synesthesia): c-sharp as blue, d-natural as yellow, and the like.

There are many categories of synesthesia: grapheme→color synesthesia, spatial sequence synesthesia, sound→color synesthesia, number form, ordinal linguistic personification and lexical→gustatory synesthesia. Those who have spatial sequence synesthesia see numbers as occupying specific locations in three-dimensional space. Ordinal linguistic personification is a condition in which an individual experiences actual personalities for ordered numbers, letters, days, and the like. (An example from Richard Cytowic’s 2002 study A Union of the Senses is a woman who says, “”I [is] a bit of a worrier at times, although easy-going; J [is] male; appearing jocular, but with strength of character; K [is] female; quiet, responsible….”)

What’s going on here, suggests the neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran, is that neural connections that run through adjacent functional areas of the brain, which are “trimmed” by the activation of certain genes in most people, are not trimmed in synesthetes. Instead of the normal separation of sound and color, for example, they remain neurologically linked, their connected synapses remaining active when most people’s don’t.

In my own experience, at the piano, I associate the feeling of different tonalities (what we usually refer to as “keys”, like C major or E-flat minor) with “personalities”. These are “personalities” not in the Jungian sense of highly-developed modes of thinking and behavior, but rather personages who embody a range of potential behaviors. As I play them, whether as an interpreter, improviser or composer, I am aware that I’m interacting with them as I would be with real people. When I start to play, I begin a “conversation” in which there’s a give-and-take between the piano keys, the particular tonality I’m in, and me. The fact that there’s an E-flat in the middle of the keyboard isn’t important in itself. If, however, I play a melody in which that black key, that E-flat, is central, then whether I’m in the tonality of E-flat major, which requires three black keys (E-flat, A-flat and B-flat) to play a diatonic scale (making the E-flat an important member of the family), or in the key of C major, which uses no black keys to play a diatonic scale (thus making the the E-flat an intruder), is a critical difference. And I’m in a constant mental dialogue with the keys and the tonalities as the music develops over time. I’m trying to shape a message, or a mood, or an experience, while the sound and the ivory are sending me suggestions as to how to proceed.

Improvising a fugue is another matter again, introducing several higher levels of complexity. First off, it is defined by a very particular beginning, middle and end. The beginning is defined by a melody (usually called a motif) that is sequentially repeated in all the musical lines (usually referred to as voices). Secondly, although harmonic modulation is typically one of the factors that gives a fugue its variety, the modulations as the voices enter in sequence in the beginning must be simple and fairly obvious. Anything too chromatic starts sounding like the middle, called the development section. The middle may introduce new melodies to create more variety. The motif may be played twice as slow or twice as fast, or even upside down or backwards, in the development section. The end section almost always features a device called a stretto, in which each voice performs the motif in a sort of one- or two-beat delay, creating something like an echo effect. The effect is more like everybody deciding to jump into the pool at almost the same time. It makes a big sonic splash, in other words. And the end almost always features broad final chords, called a perfect cadence, that telegraph the end of the piece to the listener.

Add these considerations to the relationship one already has with keys, harmonies and tonalities: one can start to appreciate the enormity of Bach’s astounding output. (And on top of all this, some scholars have detected coded messages in his motifs. What was he, the Mata Hari of Saxony?)

V.S, Ramachandran, the neurologist, has suggested that since synesthesia is many times more common in creative artists than in the general population that there is a link between the two. He hasn’t gone so far as to suggest that synesthesia is a pre-condition for artistic creativity, but you know that’s where he wants to go.

I would, on the other hand, say that in addition to synesthesia, there are many other “mutations” in the way the mind processes information that enable the kind of mental agility that results in, say, improvised fugues.

What really got me going on this jag was an account I read of Bach orally outlining how a given motif could be made into a three-part fugue. The incident, as described by James Gaines in An Evening in the Palace of Reason: Bach Meets Frederick the Great in the Age of Enlightenment (2006), concerned “Old Bach”, as he was called by his kids, sixty-two years old, brought to Berlin to meet the King of Prussia (and fellow composer) Frederick the Great. Bach’s second son, Carl Phillip Emanuel, was the court composer and the keyboard stylist in Frederick’s orchestra. Possibly to amuse themselves by making fun of the aesthetically old-fashioned J.S., C.P.E. and Frederick hustled the old man to the palace and thrust a weird, specially-composed motif at him and commanded that he improvise a three-voice fugue on it. Bach reportedly looked at it and described exactly how he was going to do it, including such improbable details as in which measures (he could say which by number) the various devices I described above as integral to fugal form would occur. Then he sat down and played it. (Bach apparently brooded about this incident afterward. Three weeks after returning home to Leipzig, he produced one of the great works of the eighteenth century, a compendium of eighteen fugues, sonatas and canons based on that weird motif, which he called, collectively, A Musical Offering. He bound the work in a gold-leaf volume and sent it off to Frederick, who never acknowledged it.)

Most composers have to sit down and methodically construct their fugues like a carpenter constructs a table. Apparently Bach did not have to do this. In fact, the evidence suggests that, similar to Mozart and Tchaikovsky, the music just “appeared” in his head, fully-formed. How could this be?

Check back tomorrow for part two of Opus 5…

Contributor Allan Greene is a New York-based composer, pianist, teacher and musical director who has collaborated with dancers for 33 years. He has been Company Pianist with Dance Theatre of Harlem and Aterballetto (Italy).

He has worked with many distinguished teachers, beginning with Valentina Pereyeslava, Leon Danielian and Patricia Wilde at Ballet Theater School; Hanya Holm, Doris Humphrey, Janet Soares, Kazuko Hirabayashi and Hector Zaraspe at Juilliard; Alvin Ailey and Judith Jamieson; and Arthur Mitchell, Karel Shook, and Bill Griffith at Dance Theatre of Harlem. At Princeton University he worked with Ze’eva Cohen, Elizabeth Keen and Jim May. He worked with Merce Cunningham at his studio in Westbeth. At New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts he has collaborated with Gus Solomons, Jr., David Dorfman, Tere O’Connor, Joy Kellman, Jolinda Menendez, Liz Frankel, Cherilyn Lavignano, Jim Sutton and Jim Martins. At the Joffrey Ballet School he has played for Francesca Corkle, John Magnus, Eleanor D’Antuono, George de la Peña, Michael Blake, Mary Ford, Alexandre Proia, Diane Orio, Brian McSween, Davis Robertson. Then there’s John Butler, William Carter, Maurice Curry, Gabriela Darvash, Agnes de Mille, Robert Denvers, Tina Fehlandt, Eliot Feld, Frederic Franklin, Cindy Green, David Howard, Stephanie Marini, Mark Morris, Dennis Nahat, Patricia Neary, Irina Nijinskaya. Francis Petrelle, Christine Sarry, Victoria Simon, Paul Sutherland, Glen Tetley, Violette Verdy, Michael Vernon. There are many others, including many Russian names he transposes with one another. Dvoravenkos, Messerers, Jouravlevs, Koslovs; and Alexander Goudonov, and now I think I’ve spewed enough.

Mr. Greene holds degrees in music (B.A., Carleton College) and architecture (B.Arch., City College of New York). He worked as an architect briefly, from 1993-1996, specializing in computer-aided design and drawing. He studied and charetted at the Instituto Politecnico of the Universidad de la Habaña in Cuba. He was awarded fellowships for musical composition by the Thomas J. Watson Foundation, and the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France. He holds a New York City #6 Boiler Operator’s License. He studied orchestral conducting at Mannes College of Music.

He has been Musical Director for several Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway productions, and has scored one film.

He has completely forgotten to mention his myriad musical compositions, many of which have been created for his wife, the violinist Juliana Boehm. Here are some of his funny titles: Talas (“rhythm” in Sanskrit), Uneasy Dream, Liebestod, Core Piece No. 1, ...awake, December, An Island in the Moon. Although there are a great many others, Mr. Greene prefers not to dwell in the past.

Mr. Greene is currently on the staffs of the Joffrey Ballet School, the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School at American Ballet Theater, The Juilliard School and NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. He is also working on a 24-year project, his sons Oliver, 9, and Ravi, 6.

In summary, Mr. Greene draws this life-lesson: Raising kids sucks up most of one’s available oxygen; fortunately, Art returns most of it.

Try www.balletclasstunes.com for your ballet and modern class music… download individual selections or complete classes directly to your mp3 player, smart phone or computer. Visa/MC/PayPal.