Heinz Spoerli’s Magnificat is challengingly intellectual and satisfyingly human. The choreographer took inspiration from the text of Bach’s “Magnificat in D major” and the arias of two Bach cantatas, “Where shall I flee” and “I have enough,” as well as from a visit to the Kolumba museum in Cologne, Germany—the art museum of the Archdiocese of Cologne.

Heinz Spoerli’s Magnificat is challengingly intellectual and satisfyingly human. The choreographer took inspiration from the text of Bach’s “Magnificat in D major” and the arias of two Bach cantatas, “Where shall I flee” and “I have enough,” as well as from a visit to the Kolumba museum in Cologne, Germany—the art museum of the Archdiocese of Cologne.

From its cerebral beginnings, Magnificat becomes more tangible with each movement. Where it tests the viewer’s mind, it rests the eyes. The scenery is minimal and geometric, the costumes are uncomplicated in structure, and the ebb and flow of the dancing allows eyes, mind, and heart to process the layers of symbolism in this work. Peter Schmidt’s set designs are imposing while remaining in harmony and conversation with the choreography.

The program notes discuss Spoerli’s interest in the conditions inherent in religious devotion: “…expression of a profound devoutness, which also involves rejection, exclusion, uncertainty, and separation.” The featured dancers in Magnificat represent and experience all these things with powerful impact.

In the opening movement (the first of ten), the stage is lit in deep blues and littered with floating balloons. Dancers costumed in white and neutral beige sit on or carry large white cubes. Gradually, they process offstage. Soon eight women wearing warm pinkish-browns begin with decorative arm gestures, then move to joyous, generous dancing through the whole space. Eventually they are joined by sixteen men, eight of whom dance a very pleasing allegro section traveling sagitally in counterpoint.

Notably in this movement (in the women especially) the dancers look unabashedly forward at the audience, even at times when other head facings seem more appropriate. (Later on, all enter looking deliberately not forward. Some appear disgruntled, arms crossed, others thoughtful or defiant. They collect downstage, and a few at a time, they sit, then all point outward. A lone man crosses stage in front of the group while none make eye contact—the ultimate exclusion.)

The stage then empties and darkens for a gloriously lit pas de deux, danced with electricity by Galina Mikhaylova and Vahe Martirosyan. They are supple and dynamic, tense without brittleness. A second duet for this couple later in the ballet evokes despair and longing and is decidedly less restrained.

The ensemble dances again, this time clad in black, snaking their way across the stage. One woman (She Yun Kim) remains separate from the group, repeatedly assaulted by their angular gestures. The visual effect created here is repeated later with a corps of men assaulting a physical barrier of triangular pillars.

Devotion is perhaps best embodied in the dances for Kim, Filipe Portugal, and Arman Grigoryan. Duets for the two men are full of power, trust, and compassionate brotherhood. Later the two are respectfully combative. Their movements are synchronized more often than not. Kim’s ethereal quality is mesmerizing. Is she mortal? Divine? The three lay hands on one another, palms flat, as if experiencing some communal magnetism. She is grounded, then on pointe, then suspended over and over by the two men.

Two pas de deux for Melanie Borel and Olaf Kollmansperger present them as an obviously human couple, in stark contrast with the tingling austerity of Mikhaylovna and Martirosyan or the transcendence of Kim and her guardians. Their duets suggest first misunderstanding, then outright conflict.

A trio of noodly women appears ominously throughout the work. Sarah-Jane Brodbeck, Juliette Brunner, and Sarah Mednick are lovely and boneless and vaguely sinister. As a group, they seem to be an entity of manipulation or fate.

The ensemble work is formidable throughout Magnificat. The corps de ballet echoes Schmidt’s set pieces and Bach’s music in form and energy. A wonderful moment happens about two-thirds through the ballet in which they parade boisterously over the stage, a triumphant congregation. The whole chorus sings as the dancers flock, circling the stage, collecting in lines and dispersing as if pulled along by the current of the “Magnificat in D major.”

At the climax of the work, all the featured dancers are finally onstage together, each group reprising its own choreography. They assemble downstage and all prostrate themselves behind Kim as the chorus sings its loudest gloria. The effect is monumental, with Kim processing slowly, purposefully, directly toward the audience. Finally, the whole flock takes one final lap and demolishes a stacked structure upstage. Humanity makes peace with itself and breaks free from its bonds on the final “Amen.”

All the intellectual and human elements of art come together to make Magnificat a film well worth watching.

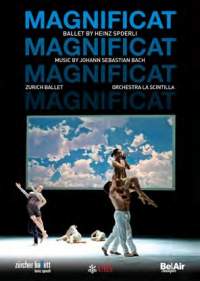

Magnificat (If Today Were Tomorrow and Yesterday Today)

Choreography by Heinz Spoerli

Music by J S Bach

Zurich Ballet

BelAir Classiques, 75 minutes