by Allan Greene

Let me get this out right up front: if you go for Arvo Pärt, you’ll love the late works of Franz Liszt.

I’ve played and loved the late Liszt since I was kid. It was in the late Sixties on a trip into Manhattan to the old Schirmer’s that I found a newly published Schirmer number called The Late Liszt. I was thirteen or fourteen and I had been composing atonal music for a few years; but as a piano student, Liszt, the Romantic, was my god. After going to considerable trouble to master his Liebestraum No. 3, I was taken by surprise that late in his life Liszt had composed these spare, non-bravura morceaux. That some were nearly atonal, un-moored from traditional harmony, made me even gladder.

I’ve played and loved the late Liszt since I was kid. It was in the late Sixties on a trip into Manhattan to the old Schirmer’s that I found a newly published Schirmer number called The Late Liszt. I was thirteen or fourteen and I had been composing atonal music for a few years; but as a piano student, Liszt, the Romantic, was my god. After going to considerable trouble to master his Liebestraum No. 3, I was taken by surprise that late in his life Liszt had composed these spare, non-bravura morceaux. That some were nearly atonal, un-moored from traditional harmony, made me even gladder.

All these years I’ve accompanied dance I’ve used pieces from that collection in classes. I have never, with one unhappy exception (Sir Frederick Ashton’s Mayerling), seen choreography to this music. This volume held, and holds, such meaning for me, its contents might almost be my autobiography. I’ve been troubled me all these years that I haven’t seen great dances to this profound music.

And then, while researching a column on Arvo Pärt, who is wildly popular with choreographers, it hit me.

Late Liszt is late Pärt. I mean, really.

Do they have a spooky, supernatural, counter-intuitive relationship, filled with seemingly strange coincidences? Let’s see. Liszt was Hungarian, Pärt is Estonian. Their native tongues are both members of the the Finno-Ugric language group. Both had an affinity for the avant-garde from the very beginning. Both suffered mid-career life changes that sent them into a quasi-religious bout of self-examination.

Except for the “dark night of the soul” that each went through, the coincidences don’t prove much. Liszt was a very public figure who set the People Magazine standard for celebrity and scandale in his day; Pärt is a private person, thrust into the public eye by his success translating his privacy into music. He has a stable home-life and a happy family.

But it is extraordinarily interesting to me these two composers more than a century removed from one another cross paths at a very particular point in their artistic journeys, after having gone through depression and soul-searching. The fact that Pärt has become so popular among choreographers and Liszt is not tells me something is wrong.

I’m going to right that wrong.

Initially, I’d like to suggest that Pärt may have led us to the edge of an age of Radical Diatonicism, much as Liszt blazed a path to radical chromaticism 150 years ago.

Diatonic versus Chromatic

It is a bit easier to follow my thesis if we understand the historic relationship between the diatonic (white-key) scale and the chromatic (all the keys on the piano) scale.

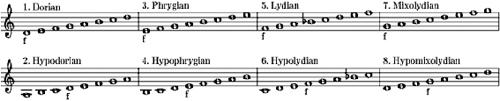

The diatonic scale held absolute power in Western music at least as far back as the 12th Century, when the earliest surviving notated music, that of the monk Perotin, was composed. Music was organized around seven tones, what we today call A, B, C, D, E, F and G. Music was characterized based on which of those seven tones dominated the melody. Depending on which tone it was, the music had a certain sound, called a mode (modus). What we today call a major scale was called the Lydian Mode. What we today call the minor scale (or natural minor scale) was called the Hypodorian (or Aeolian) Mode. There were eight modes, the most dissonant being the Phrygian and Hypophrygian or Lochrian.