by Emily Kate Long

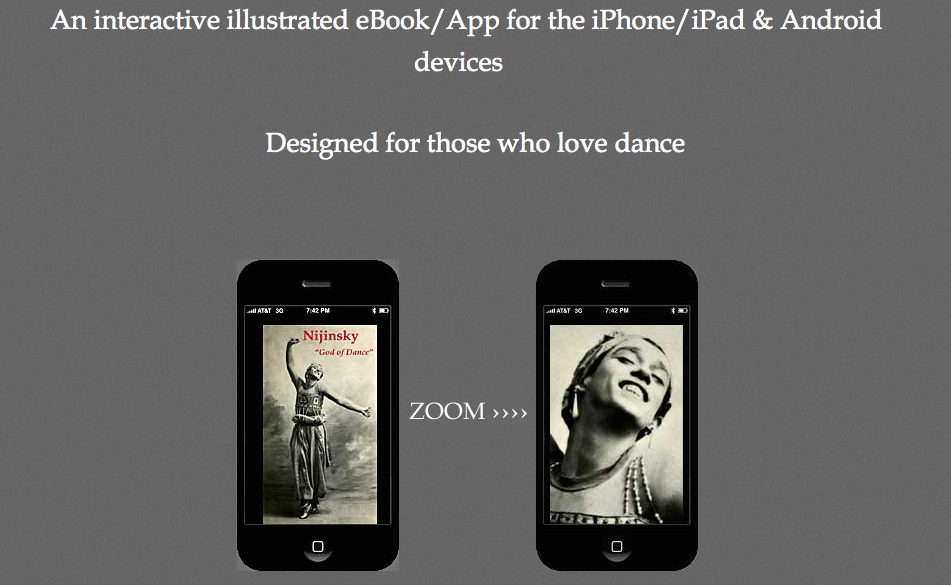

(An app/ebook for iPhone, iPad, and Android devices)

No film footage is known to exist of the legendary dance enigma Vaslav Nijinsky. Photographs and written accounts are all that remain to document Nijinsky’s impact on audiences of his time and to inspire artists today. Nearly 250 such photos are thoughtfully and lovingly presented in the ebook Nijinsky: God of Dance, curated by Pryor Dodge.

The images come from the collection of Roger Pryor Dodge, a dancer and commentator of the arts who amassed this photographic treasure trove over the course of many years after seeing Nijinsky perform in 1916. Portions of the collection have been published in Romola Nijinsky’s 1934 Nijinsky and in Lincoln Kirstein’s 1975 Nijinsky Dancing. Dodge donated his photos to what is now the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center in 1937, and his son’s development of this ebook gives users access to the full collection.

The app is sensibly arranged, with the photos organized into several subcategories. One is a series of thumbnails of the whole collection where users can select particular photos, zoom in and out, or simply browse one captivating image after another. There is also a menu listing the photos by ballet, including details of the ballet’s production and performance and, in some cases, commentary. The app also contains a number of non-dance portraits and photos of Nijinsky’s personal and student life.

In addition to the photographs, the ebook includes a small selection of relevant commentary by Roger Pryor Dodge, Edwin Denby, Tamara Karsavina, and Daniel Gesmer. The writings provide some really interesting background on the process of photography itself during Nijinsky’s time, as well as insight into elements of his artistry as both a dancer and model. There’s also a link to a short film from the exhibition Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes 1909-1929: When Art Danced with Music.

I downloaded this app to my iPhone, and the images translate well to its small screen. No clarity is lost using the zoom feature, and I haven’t stopped poring over all the fascinating details of weight, expression, and the dynamic arrangement of Nijinsky’s poses. In reading the accompanying articles, I found an even greater appreciation for the photos themselves. For about six dollars, any dancer can (and should) have this collection at his or her fingertips. It’s a valuable and enjoyable user experience as far as the technology is concerned, but more importantly, in giving the public access to the small tangible portion of Nijinsky’s transformative legacy.