by Allan Greene

(If you haven’t read Part I of this two-part series, please start here)

The case of Scott Flansburg

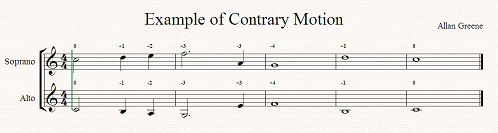

Having improvised fugues and constructed them on paper piece by piece, I have a pretty good sense of what mental operations are required to make one. It’s not a knee-jerk assumption to assert that arithmetic operations are central to assembling a fugue. The first voice “sings” the motif for x number of bars, the second voice enters with the motif for x + (x ± 1)bars at the interval of a perfect fifth, then the third voice repeats the entrance of the first voice, an octave lower; in the meantime, the other voices are doing separate melodic figurations which are in harmony with each other and the third voice… and this is just the beginning (of a three-voice fugue). Some restatements of the motif are of a duration of x/2 or 2x; some passages have voices in parallel at the interval of a major third or a major sixth; some passages have voices moving in contrary motion (Voice 1 moves +1, +2, +3, -3, -4, +1, while Voice 2 moves -1, -2, -3, +3, +4, -1). You get the idea… a lot of arithmetic.

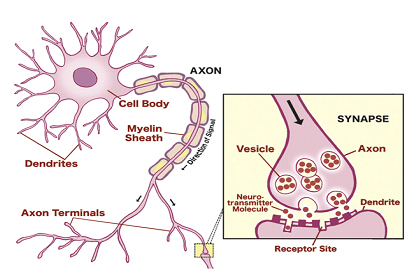

So the areas of the brain that are involved in addition and subtraction are engaged in the creation of fugues. My conjecture, building on Ramachandran, is that some neural wiring is shared by arithmetic-processing areas and music-processing areas of the brain. So I went in search of Brodmann areas identified with the two.

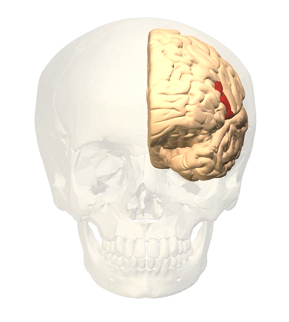

According to the Wikipedia, “Together with left-hemisphere B[rodmann]A [rea]45, the left hemisphere BA 44 comprises Broca’s area a region involved in semantic tasks. Some data suggest that BA44 is more involved in phonological and syntactic processing. Some recent findings also suggest the implication of this region in music perception…”

From The calculating brain: an fMRI study, a 2000 article in Neuropsychologia by T.C. Rickard, et al, of the Department of Psychology, University of California, San Diego: “For the arithmetic relative to the other tasks, results for all eight subjects revealed bilateral activation in Brodmann’s area 44…Activation was stronger on the left for all subjects, but only at Brodmann’s area 44 and the parietal cortices. No activation was observed in the arithmetic task in several other areas previously implicated for arithmetic, including the angular and supramarginal gyri and the basal ganglia.” (My boldface in both quotes.)

So in most test subjects, music and math undergo processing in at least one shared area, possibly. But what about Bach’s instantaneous mental picture of the completed fugue?

A clue to the answer to that question is further down in the Wikipedia article. Under the rubric Trivia, we read: “Scott Flansburg of San Diego, California is a “human calculator” who can perform complex arithmetic in his head. Interestingly when his brain was scanned while doing complex calculations using fMRI; which was recorded for the show Stan Lee’s Superhumans; his brain activity in this region was absent. Instead he showed activity somewhat higher from area 44 and closer to the motor cortex.”

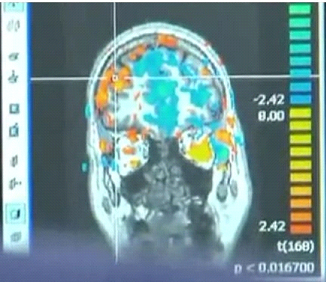

I looked at the clip on YouTube. Mr. Flansburg, a rather ordinary-looking middle-aged guy from Herkimer, New York who has the extraordinary ability to mentally calculate dates, arithmetic operations, square- and cube-roots, and who-knows-what-else faster than any computer, is tested while being recorded by an fMRI at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. The surprise in the results is that Mr. Flansburg barely uses Area 44 when doing his mental calculations. The imaging shows the brain activity during his calculations mostly in areas of visual processing, areas that are unique to human brains and have appeared very recently in the evolution of the human brain.

Is it possible that the lightning speed of Scott Flansburg’s calculations and J.S. Bach’s fugue-composing related to the same brain activity as normal human visual object recognition? Is one aspect of musical genius caused by a rare variant in neural activity?

Modern Dance and Imitative Counterpoint

This was Louis Horst’s insight about composing dances: that since they are intimately entwined with music they should be constructed as music is constructed. This belief led inevitably to Bach. It is Bach, after all, whose 335 four-part hymn arrangements form the model for all the theory and all the rules for writing musical voicing. It is Bach who pretty much wrote the book on writing music in all tonalities (The Well-Tempered Clavier, Books I and II). It was Bach who invented the piano (keyboard) concerto (Brandenburg Concerto No. 5). It was Bach who in 1736 suggested improvements on the very new keyboard instrument called a piano e forte which set it on its course to take over all of Western music. Bach’s innovations could fill pages. Bach was, and is, considered by many to be the fountain from which all subsequent music sprang.

As such, many subsequent “rules” for how to write music are based on autopsies of Bach’s works. In a simplified way, Horst adapted these rules to dance movement. He called choreography “dance composition”. His results were remarkably successful. His Wikipedia listing gives an idea of his influence: “…Apart from being a personal friend and mentor to [Martha] Graham, Horst worked and wrote scores for many other choreographers, including: Ruth St. Denis, Ted Shawn, Helen Tamiris, Martha Hill, Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman, Agnes de Mille, Ruth Page, Michio Ito, Nina Fonaroff, Adolph Bolm, Harald Kreutzberg, Pearl Lang, Jean Erdman [and] Anna Sokolow, Horst’s assistant and demonstrator.”

Uncut Diamonds in the Scanner

Are there in the wide world of dance today current or future choreographers whose minds are wired in meaningfully different ways from those of the preponderance of their colleagues? Uncut diamonds who compose or will someday compose dances fully-formed in their heads, of such beauty as mathematical logic?

We should be on the lookout, brain scanners at the ready.

Contributor Allan Greene is a New York-based composer, pianist, teacher and musical director who has collaborated with dancers for 33 years. He has been Company Pianist with Dance Theatre of Harlem and Aterballetto (Italy).

He has worked with many distinguished teachers, beginning with Valentina Pereyeslava, Leon Danielian and Patricia Wilde at Ballet Theater School; Hanya Holm, Doris Humphrey, Janet Soares, Kazuko Hirabayashi and Hector Zaraspe at Juilliard; Alvin Ailey and Judith Jamieson; and Arthur Mitchell, Karel Shook, and Bill Griffith at Dance Theatre of Harlem. At Princeton University he worked with Ze’eva Cohen, Elizabeth Keen and Jim May. He worked with Merce Cunningham at his studio in Westbeth. At New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts he has collaborated with Gus Solomons, Jr., David Dorfman, Tere O’Connor, Joy Kellman, Jolinda Menendez, Liz Frankel, Cherilyn Lavignano, Jim Sutton and Jim Martins. At the Joffrey Ballet School he has played for Francesca Corkle, John Magnus, Eleanor D’Antuono, George de la Peña, Michael Blake, Mary Ford, Alexandre Proia, Diane Orio, Brian McSween, Davis Robertson. Then there’s John Butler, William Carter, Maurice Curry, Gabriela Darvash, Agnes de Mille, Robert Denvers, Tina Fehlandt, Eliot Feld, Frederic Franklin, Cindy Green, David Howard, Stephanie Marini, Mark Morris, Dennis Nahat, Patricia Neary, Irina Nijinskaya. Francis Petrelle, Christine Sarry, Victoria Simon, Paul Sutherland, Glen Tetley, Violette Verdy, Michael Vernon. There are many others, including many Russian names he transposes with one another. Dvoravenkos, Messerers, Jouravlevs, Koslovs; and Alexander Goudonov, and now I think I’ve spewed enough.

Mr. Greene holds degrees in music (B.A., Carleton College) and architecture (B.Arch., City College of New York). He worked as an architect briefly, from 1993-1996, specializing in computer-aided design and drawing. He studied and charetted at the Instituto Politecnico of the Universidad de la Habaña in Cuba. He was awarded fellowships for musical composition by the Thomas J. Watson Foundation, and the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France. He holds a New York City #6 Boiler Operator’s License. He studied orchestral conducting at Mannes College of Music.

He has been Musical Director for several Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway productions, and has scored one film.

He has completely forgotten to mention his myriad musical compositions, many of which have been created for his wife, the violinist Juliana Boehm. Here are some of his funny titles: Talas (“rhythm” in Sanskrit), Uneasy Dream, Liebestod, Core Piece No. 1, ...awake, December, An Island in the Moon. Although there are a great many others, Mr. Greene prefers not to dwell in the past.

Mr. Greene is currently on the staffs of the Joffrey Ballet School, the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School at American Ballet Theater, The Juilliard School and NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. He is also working on a 24-year project, his sons Oliver, 9, and Ravi, 6.

In summary, Mr. Greene draws this life-lesson: Raising kids sucks up most of one’s available oxygen; fortunately, Art returns most of it.

Try www.balletclasstunes.com for your ballet and modern class music… download individual selections or complete classes directly to your mp3 player, smart phone or computer. Visa/MC/PayPal.