Happy New Year!

This month one of our guest authors is Donna Krasnow, PhD, a long-time leader and researcher in dance medicine and science. One of her areas of specialization is Motor Learning —i.e, how the body learns movement. There are many aspects to the recent research in this field that are helpful for dancers / teachers to be aware of, so Donna’s article is a welcome addition to our growing list of topics to share with you.

As always, if you have any comments / questions, we would love to hear from you! – Jan Dunn, Dance Wellness Editor

________________________________________________________________________

Motor Learning In Dance

by Donna Krasnow, PhD

When we look at how dancers move and how they learn to dance, we sometimes call this motor behavior. One area of motor behavior is known as motor development. This answers questions about how we change from birth to our senior years. For example, anyone who has taught young children will know that the 3-4 years olds can gallop and hop, but most cannot skip yet. By the time children are 6 years old, most can skip, as they have developed enough motor control to do this complex task.

Motor control tells us how the brain can plan and direct our movement. One example of this is what we call muscle synergies, or how groups of muscles learn to work together. Some of these synergies are learned through our natural development, such as the easy oppositional swing of the arms to the legs in everyday walking. Some are specific to dance, such as moving through space maintaining turnout, or learning to lift the arms overhead while keeping the shoulders down.

What is motor learning?

Motor learning is the area of study that looks at how the dancer learns new movement, but not just in a single class or practice session. When we use the term motor learning, we are referring to changes that are learned through practice and are permanent, or “remembered” on some level, even if that remembering is not something we are aware of. Simply being able to do something new for a minute in class does not mean it has been learned, as all teachers know!

The learning process

What affects how dancers learn? We know that individuals have different learning styles:

- Some learn visually, and need to see demonstrations to learn well.

- Others need verbal instructions or explanations to do their best.

- Some are what we call “kinesthetic”, and need hands-on information, or touch.

The most effective teachers use a variety of ways to present and instruct, and dancers who can learn how to broaden their learning styles will be able to work with many different teachers and choreographers.

Demonstrating

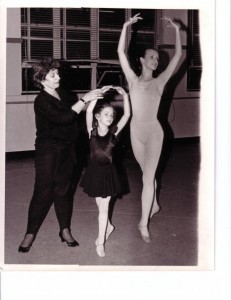

Most dancers, especially beginners, need to see demonstrations of new material, or material they want to improve. With demonstrations, dancers can see how the different body parts organize, how the movement fits rhythmically with the music, how the body orients in space, and many other important aspects of the movement. Often it is best to let the dancers see one or more demonstrations, try the combination first, and then give them additional instructions. We know from the research in motor learning that it is very easy to overload the dancer, especially the beginner, with too much information at the start of learning new material, and this will hinder rather than aid learning.

Giving feedback

So what about feedback after material has been seen and attempted? First let’s look at when feedback should be given, and how often. We can give feedback to dancers, usually called corrections, during their movement or after they have done the combination. If feedback is being given while the dancer is moving, it is important that it enhances or adds to what they are already doing, rather than try to get them to completely change their efforts. For example, during a series of leaps, one could say “Yes, stretch your legs even more, and lift up through the top of your head!”

Corrections that are intended to make a shift or change should be saved for the time between attempts. This might include a change in timing, or a change in the positioning of the arms during the movement, or a total shift in spatial direction. It is very difficult for the dancer to make a change in approach or strategy while in motion, as it demands too much attention. This might actually cause a deterioration in the skill.

When it comes to the question of “how often” we should give feedback, the traditional view was “the more the merrier”. We now know that constant feedback is not as useful as giving dancers the opportunity to have time to practice without ongoing information. It allows what we call problem-solving time, and in the long run makes the dancer a better learner and a stronger dancer.

When it comes to the question of “how often” we should give feedback, the traditional view was “the more the merrier”. We now know that constant feedback is not as useful as giving dancers the opportunity to have time to practice without ongoing information. It allows what we call problem-solving time, and in the long run makes the dancer a better learner and a stronger dancer.

What do we know about the nature of feedback? Should it be about what the dancer is doing wrong, or should we praise what they are doing correctly? The answer to this question is both, but for different reasons! In order to improve, dancers need to hear what they are doing wrong (known as error detection) in order to make changes. More advanced dancers can often figure this out themselves, but beginners need help with this. This does not mean that the teacher’s tone needs to be harsh or insulting or demeaning. Feedback can be given is a supportive and encouraging voice.

On the other side of things, praise and recognition of what is being done correctly is extremely important for motivation. While it will not improve the skill level per se, it will encourage the dancer to continue practicing, and to feel confident about his or her work. And this will, in the end, improve the dancer’s abilities.

A word about video

Does it help dancers see themselves on video? There is a lot of controversy about this process. One thing we do know is that if beginning dancers are going to look at video of their dancing, the instructor needs to be present to point out what the dancers can learn from their observations, and how to improve their next attempts. Seeing video with no educated information is not that useful as a learning tool.

Effective practice

Another important subject that motor learning researchers look at is retention. Since learning is about making new information and skills relatively permanent, how do dancers retain information? Clearly dancers need a great deal of practice, practice, practice. It can take hundreds if not thousands of hours to learn a body of dance skills. However, a few boundaries should be observed.

First, constant practice without feedback can be detrimental. If the dancer is practicing something incorrectly, then this error will become permanently imbedded in the skill! We hope to guide the dancer towards more effective execution with each practice.

Second, practice should never be pushed to the point of fatigue and injury. Rest is an important part of the big picture, and we know that even during sleep, the brain continues to process new information and learn.

Third, practice needs variety. Try doing the skill at different speeds, with changes in the space, with different arm or leg gestures, and even with different emotional intention. Variety challenges the motor system. Although it may seem that practicing a skill the same way over and over leads to the best learning, this is a myth. Varying the skill may at first look awkward and confused, but in the long run, it results in better learning. And let’s not forget that variety is a great way to avoid boredom and keep the dancer attentive. Without attention, there is no learning.

Learning on right or left?

Another issue that has come up in the study of dance and motor learning is the question of laterality, or on what side should we be learning new material, right or left? Recent articles in dance have suggested that we should be learning on the left (non-dominant) side first, at least some of the time. Interestingly, when we look at the research on this in other fields, what we know is this: First, there is learning transfer, so if you learn something on the right, some of that information is automatically learned on the left, and vice versa. Second, that transfer is stronger when you learn on the dominant (right for most) side first. This seems to contradict what the dance writers are saying.

Another issue that has come up in the study of dance and motor learning is the question of laterality, or on what side should we be learning new material, right or left? Recent articles in dance have suggested that we should be learning on the left (non-dominant) side first, at least some of the time. Interestingly, when we look at the research on this in other fields, what we know is this: First, there is learning transfer, so if you learn something on the right, some of that information is automatically learned on the left, and vice versa. Second, that transfer is stronger when you learn on the dominant (right for most) side first. This seems to contradict what the dance writers are saying.

I would suggest that the problem is not that we learn on the right side first, but that due to class procedure, this gives the dancers far more practice on the first side. Often the teacher will demonstrate on the first side (while many dancers are following along), then give verbal information (while dancers practice), then mark it on the first side, then finally do it full out on the first side. Then the dancers might do a quick mark on the second side, and do the combination. This process is biased towards much more repetition on the first side. Teachers need to ensure that there are extra attempts on the second side, to even out the practice.

Using mirrors

One other learning tool that is fairly universal in dance is the use of mirrors. Again, this is an area of controversy. What do we actually know? There is some research that suggests that learning is faster using mirrors, but less is retained or remembered the next day, or in future days. More importantly, learning with the mirror may actually be detrimental to kinesthetic learning, that is, the dancer knowing from “feel” how to do something. In a study with athletes who worked with mirrors, they were practicing how to keep the knee aligned with the foot to prevent injury (sound familiar?). When they turned away from the mirror, their errors (knee going off the correct line) increased by 50%. Ouch.

A final word

The last controversial topic I will mention is how we use language to give instruction. As tempting as it is, bringing dancers’ attention to a specific muscle while they are dancing is generally not a useful approach. It is better to describe movement outcomes or goals, and let the brain select the muscles. This can be done in a variety of ways, including describing movement shaping (draw a large arch on the floor with your foot as your body lengthens vertically), or using metaphor (lift up your chest and eyes as you open your arms as if you want the sun to warm your upper body), or anatomical imagery (imagine your shoulder blades sliding down your back like they are melting as your arms are going up to 5th position).

Teachers are creative artists who can draw on their years of expertise and imagination to create a class that draws on all of the current motor learning ideas while maintaining the beautiful traditions of our art form.

BIO: Donna Krasnow, PhD, is a Full Professor in the Department of Dance at York University in Toronto, and a lecturer at California State University, Northridge, and California Institute of the Arts. For the past thirty years she has worked professionally as a choreographer, performer, dance educator, and researcher. She was founding Artistic Director for Möbius Dance Company in San Francisco, and has performed and taught extensively in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Japan. Donna has performed with Footloose Dance Company (San Francisco), Daniel Lewis Repertory Dance Company (New York), Northern Lights Dance Company (Toronto) and as performing as a guest artist with Bill T. Jones / Arnie Zane Dance Company in its 1990 Toronto season. She is noted for her teaching of the José Limón technique and has taught for the José Limón Dance Institute in New York. Donna was head of the modern division at the Canadian Children’s Dance Theatre in Toronto from 1988-2007, where she has developed a curriculum for young dancers (10-18 years old) integrating Limón technique, improvisation and composition.

Donna specializes in dance science research, concentrating on dance kinesiology, injury prevention and care, conditioning for dancers, and motor learning and motor control, with a special emphasis on the young dancer. She was the Conference Director for the International Association for Dance Medicine and Science from 2004-2008, and served on the IADMS Board of Directors from 1996-2008. She has also served on the Board of Directors of the Performing Arts Medicine Association, and was a founding member of Healthy Dancer Canada. Donna conducts workshops for professional dance teachers in alignment and healthy practices for dancers, including the Teachers Day Seminars at York University, Arts Umbrella in Vancouver, and a nine-time resident guest artist at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne, Australia. She has been a keynote speaker for professional dance associations such as Cecchetti Australia, and an invited speaker for A Day for Teachers, sponsored by IADMS, on several occasions. She regularly consults on curriculum development for various colleges and universities. In addition to being a GYROTONIC trainer since 2005, Donna has created a specialized body conditioning system for dancers called C-I Training™ (conditioning with imagery). She has produced a DVD series of this work, and in 2010 published the book Conditioning with Imagery for Dancers with co-author Jordana Deveau. Information about the dvds and the book can be found at www.citraining.com. ; She has also published extensively in the Journal of Dance Medicine and Science, Medical Problems of Performing Artists, and Journal of Dance Education, as well as invited author for three resource papers for IADMS, in collaboration with Dr. Virginia Wilmerding. Donna completed her PhD in 2012 doing biomechanics research on dancers through the University of Wolverhampton in the UK, and is currently working on a new book on Motor Learning for Dancers with Dr. Virginia Wilmerding for Human Kinetics.