This month I’m offering you some thoughts on turn-out, that often-debated subject in dance (especially ballet) that we all worry over / strive for / get obsessed with. I am especially indebted to long-time dance medicine colleague and researcher, Dr. James Garrick, MD, for his insightful comments on this article–and a special “thank you” also to Dr. Matthew Wyon, PhD – Research Centre for Sport Exercise and Performance @ University of Wolverhampton (UK) / Vice President of IADMS, for his input as well.

Enjoy–and Pass It On!

– Jan Dunn, MS, Dance Wellness Editor

OK, so let’s talk about turn-out…that elusive external rotation of the legs in the hip socket that dancers (especially ballet dancers) all strive for.

This post is going to be just a brief foray into that (often thorny) discussion. I’m not going to give you detailed anatomical information–there are various online resources (as well as books) especially written for dancers that can give you excellent, very specific anatomical detail (I’ve provided a partial resource list at the end).

What I do want is to share with you what I feel is important for every dancer / teacher (and parent) to know–gleaned from 40 years of teaching dance / 35 years in the dance medicine field / 32 years of teaching Anatomy, Kinesiology, and Injury Prevention to dancers in university dance departments.

Just the Basic Facts, Ma’am

Turn–out, as every dancer and teacher knows, involves rotating the legs outward from the hip socket. It enables us to be able to have full range of movement in dance, especially in sideways directions.

A Brief History of Turnout

For many years, the desired “perfect” turn-out meant (especially in ballet) that you had your feet completely turned out, straight side to side, in a 180 degree straight line. But unfortunately…

Very few people have a hip socket that is capable of rotating the femur (thigh bone) completely out to the side–so the extra slack instead gets transferred to the knee joint and foot (for a full detailed analysis of how this all works, see some of the resource articles mentioned at the end). This is called, as you probably know, “forcing” your turn-out–which means that you are using compensatory movements at the knee, foot (rotation / twisting), or lumbar spine (hyperextension, or “swayback”) to increase the apparent range of your turn-out.

The problem is–if dancers “force” their turn-out from the knees / ankles / lumbar spine, not-nice things can result, especially over time.

More Basics

The structure of our hip joint is something we are born with—different factors determine how much / how little turn-out we have at the actual joint. For example:

- The shape of the bones

- How deeply set into the hip socket the femur (thigh bone) is

- How tight or loose the ligaments are

You will find some online sites that say you can possibly change your structural, inherited turn-out with early training (between ages 8-12), but this is still very much debated in the dance medicine and science field, and some of the people who are most knowledgeable about this, from a research perspective, do not think it is really possible.

What can be changed, however, is muscle imbalance–both strength and flexibility–around the hip joint, which can limit hip external rotation.

Interested? Read on!

The average person on the street usually has turn-out in the range of 40-45 degrees. We know that dancers usually average around 55 degrees, and occasionally slightly more–but very few people have that 90 degree turn-out in the hip socket that equals 180, when the heels are together in 1st position.

So when you see dancers standing at the barre in 180-degree first position, the chances are pretty good that they are “forcing” it, and taking the extra stress in the knees and feet.

Why Forcing Turnout Is Not Good

Over time, forcing turn-out puts undesirable force and pressure on joints / body parts that were not designed to do that–in particular, the feet / knees / lower back.

Be aware that there are some dance blogs that will tell you that’s it OK to do this (force at the knee / foot / lumbar spine), but those sites are ignoring the majority of the dance medicine research–which tells us that it is potentially detrimental and injurious to those body parts, over time. To quote well-known dance science researcher / author, Karen Clippinger, MS, in her textbook “Dance Anatomy and Kinesiology” (Human Kinetics, 2007):

“Failure to maintain turnout at the hip and excessive twisting from the knee down are believed to be a contributing factor to many injuries of the knee, shin, ankle, and foot”.

Other prominent researchers in this area will all tell you the same thing–and add injuries of the lower back to the list as well.

Interesting Things To Know About Turnout

Turn-out Tests

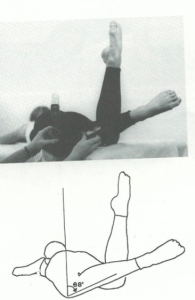

Testing how much turn-out you actually have at the hip socket should ideally be done by a dance-familiar physical therapist or trainer (or physician).

There is one prone (lying on your stomach) “eyeball” test that I like to use, which can give you / your teacher a fair idea of where your range falls–and while physical therapists would use a goniometer (the instrument used to measure joint angles) to give an exact reading, it is possible to use this same test to give an approximate estimate of the dancer’s hip external rotation.

Muscular Imbalance Issues

I mentioned above how muscle imbalance can affect your turn-out (remember our article on Causes of Injuries? – the importance of muscle balance….?). If the muscles on one side of the joint are stronger (or less flexible) than the other, it will limit full range-of-motion for that leg, in all directions–including turn-out.

It’s important to note that the hip internal rotator muscles are weak and tight in many dancers (especially ballet)—and that this will limit the amount of external rotation that can happen. Dancers can sometimes increase their measured degree of turn-out by as much as 20 degrees when they do have this imbalance situation and are put on a program for stretching and strengthening the internal rotators.

And sometimes, you aren’t actually using all the natural turn-out that you do have, simply because the external rotator muscles aren’t strong enough to hold it. So that principle of equal muscle strength and stretch is really important here…and remember that weak muscles = tight muscles.

We usually have one leg that naturally has more turn-out than the other–but be aware that muscle imbalance can also make that happen as well (here is where you need a PT to do some analysis / muscle testing). Assuming that there actually is a structural difference between R and L (there is with me, as with many dancers), you should never try to force the lesser-turned out leg to match the greater one. That will only lead to more problems down the road. Determine which of your legs is less–for example, R is 55 degrees, and L is 50–and then always match your legs to that lesser angle, to avoid stress and potential long-term injury.

Turnout In Performance?

Research in dance medicine has shown that in performance, we don’t use the same amount of turn-out as we do in class–we use less. This begs the question: If this is indeed the case, why do we insist on emphasizing extreme turn-out in class, when it does not transfer to performance?

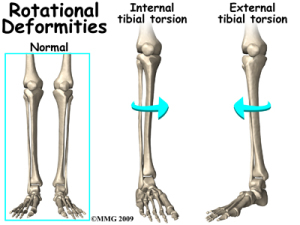

Tibial Torsion Issues

We are often told that in a well-aligned turn-out position (i.e not forcing), we should aim our “knees over toes” – specifically, the 2nd toe (or the joint space between the 2nd/3rd toe, which is the center of the forefoot).

We are often told that in a well-aligned turn-out position (i.e not forcing), we should aim our “knees over toes” – specifically, the 2nd toe (or the joint space between the 2nd/3rd toe, which is the center of the forefoot).

This is indeed correct for a leg that has a straight tibia (shinbone) – but if you are among the dancers who have tibial torsion (where the tibia rotates inward slightly, with a slight curve to the outside of the leg), that knee / 2nd toe alignment doesn’t quite match up.

There is nothing wrong with tibial torsion–it is just a different structure than a straight-line tibia–but it is important to know about, as both a teacher and dancer. (In dance screenings that I’ve participated in, as many as 40-50% of students had this type of leg structure).

Dancers with this type of anatomy often need to line the knee up with the great toe, as opposed to the 2nd, or between 1st / 2nd toe joint–as opposed to 2nd / 3rd. Forcing the knee over to the 2nd toe can cause supination (rolling outwards) in the foot, and additional problems at the knee joint.

It’s best to work with a knowledgeable dance teacher / trainer / physical therapist, if you have this type of leg alignment so that you can find the optimum position for your own individual structure.

Last, But Not Least, Turn-In!

Having a lifetime in dance and preventing injury is what it’s all about, and in that light, listen up, folks:

Turning in is equally important for dancers–maybe more so than turning out. It’s the imbalance around the joint that leads to injury, remember? So if you’re only always turning out (as many ballet dancers do) and never doing exercises in parallel, or more importantly, turn-in, you aren’t really using some of the important muscles around both the hip and knee joints…and that pre-sets us up for injuries down the road.

Plus, an important thing to realize is that those turn-in movements are keeping our actual hip joint healthy, over long years of use. It is full range of motion in any joint that keeps it healthy, and works to avoid arthritis. By only doing turn-out movements, and never / rarely doing parallel / turn-in, we are ignoring a good segment of the joint capsule…and joints that don’t move fully develop arthritis way faster than joints that move all through their natural range of motion!

So if your dance environment doesn’t provide good opportunities to use turn-in, find outside activities like Pilates, that will help keep your body in good overall balanced strength and flexibility.

And Remember–Turn-Out Doesn’t Make or Break You As A Dancer

There are so many things that all come together to make a good dancer. It’s not only the body we are born with, but the training, the artistry, the personality, the musicality…the list could go on and on.

Dr. James Garrick, MD, one of the pioneers of dance medicine, long-time physician for the San Francisco Ballet (among other companies), and researcher on turn-out, always counsels dancers to not get hung up on how much turn-out they do or don’t have. He reminds them that some of the world’s greatest dancers do not have that magical 180 degrees, and that working within your own natural turn-out, and focusing instead on all the many things that make us beautiful dancers–is what’s really important.

So – dance on – and don’t force your turn-out!

Resources for further reading

There are many sites that discuss turn-out online–here are some that I like:

The Truth About Turnout | Dance Spirit

www.dancespirit.com/2010/10/the_truth_about_turnout/

Understanding True Turnout In Dance | Dance Advantage

Centerwork: Understanding Turnout – Dance Magazine – If …

Turnout for Dancers: Hip Anatomy and Factors Affecting …

(Editors Note: this is an extremely detailed anatomical description)

Books:

“Dance Anatomy and Kinesiology” – Karen Clippinger –Human Kinetics, 2007

“Dance Medicine Head to Toe: A Dancer’s Guide to Health” – Judith R. Peterson, MD – Princeton Book Company, 2011

“Finding Balance” Fitness, Training, and Health for a Lifetime in Dance” (2nd Edition) – Gigi Berardi – Routledge, 2005

Editor Jan Dunn is a dance medicine specialist currently based on the island of Kauai, Hawaii, where she is owner of Pilates Plus Kauai Wellness Center and co-founder of Kauai Dance Medicine. She is also a Pilates rehabilitation specialist and Franklin Educator. A lifelong dancer / choreographer, she spent many years as university dance faculty, most recently as Adjunct Faculty, University of Colorado Dept. of Theatre and Dance. Her 28 year background in dance medicine includes 23 years with the International Association of Dance Medicine and Science (IADMS) – as Board member / President / Executive Director – founding Denver Dance Medicine Associates, and establishing two university Dance Wellness Programs

Jan served as organizer and Co-Chair, International Dance Medicine Conference, Taiwan 2004, and was founding chair of the National Dance Association’s (USA) Committee on Dance Science and Medicine, 1989-1993. She originated The Dance Medicine/Science Resource Guide; and was co-founder of the Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. She has taught dance medicine, Pilates, and Franklin workshops for medical / dance and academic institutions in the USA / Europe / Middle East / and Asia, authored numerous articles in the field, and presented at many national and international conferences.

Ms. Dunn writes about dance wellness for 4dancers and also brings in voices from the dance wellness/dance medicine field to share their expertise with readers.

Hi,

First of all many thanks for this informative article about the myths and true facts on this hot topic. Fantastic!

In this regard, I would have a question on how to teach turn-out or feet positioning of young dancers who have a hypermobility of the knee (knee in straight legs curves backwards). What is the healthiest option here and how can I improve the awareness of a correct alignment for the students or strengthen their postures such as to avoid overcompensation or long-term injury and nurture a well conditioned mindset about their own turn-out?

Warmest wishes from London

Aloha London — and thank you for your excellent question. Dancers with hyperextended knees are definitely a concern, and it is a topic about which I’ve wanted to do a separate article for some time –your question has spurred me to put that high on the calendar for 2015 !

But for now — hypermobile dancers need to retrain knee positioning, to understand that “locking” the knee all the way back, into the hyperextended / “swayback knees” position is NOT a straight knee. A truly straight knee, biomechanically, is one which is 180 degrees straight, where the tibia (shinbone) and femur (thigh bone) are completely lined up. The body CAN be re-trained to understand this –the muscles and proprioceptors (the sensory organs in our joints and muscles which inform us of our positioning in space) can learn that 180 position, and eventually it can become automatic for the leg to go there, instead of all the way back into hyperextension.

Ideally, your dancers could work with a dance-specific physiotherapist or dance trainer, and in London, you have great resources immediately available to you —- through Dance UK’s Healthier Dancer Programme. I would strongly recommend you connect with them — specifically with Erin Sanchez, co-director of the program.

In the meantime, one cue I immediately use when working to help dancers re-learn what “straight” means, is to keep the heels together in 1st position (I would have first determined what their approximate turn-out is, using the prone test mentioned in the article):

If you ask a dancer who has knee hyperextension to straighten their knees in 1st position, they will almost always lock them back into the “sway-back” position –and you will notice that their heels have to come apart — it is not possible to keep them together when one goes into knee hyperextension. If you ask them to plie in lst, and to straighten their knees KEEPING THE HEELS TOGETHER, they cannot go into hyperextension — they will be able to achieve the biomechanically-correct straight 180 degrees. This will start teaching them to understand what “straight” really means (along with other ways to address hyperextension). Straightening the knee in this manner will use much more of the knee extensor muscles (the ones that straighten the knee — the quadriceps, on the front of the thigh), and also the adductors (inner thigh muscles).

The only exception to a dancer being able to keep the heels together in lst / straighten to 180 is if they have extremely muscular calf muscles (the gastrocnemius) — which you may see especially in male dancers — i.e, the bulk of the calf muscle literally gets in the way, and the heels have to come apart to reach 180 in the knees. But the vast majority of dancers CAN keep the heels together and get that 180 straight in the knees.

I hope this has helped — and thank you again for bringing it up !

Thanks so much for this article! I teach young children ballet and found the information very useful. Part of my mission as a ballet instructor is to create healthy dancers, physically & mentally. Having a reasonable expectation for turn out and especially practicing the turn in was wonderful information. Thanks again!!!

Thank you Jennifer for your comment! It’s great to know that this piece was helpful. Stay tuned–we’ll have more excellent dance wellness posts coming up!