by Emily Kate Long

by Emily Kate Long

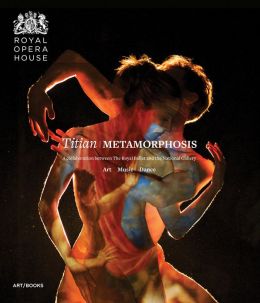

What do an industrial robot, a Renaissance master, and an astronaut have in common? Last year, all three made appearances in London’s National Gallery and the Royal Opera House as part of a project titled Metamorphosis: Titian 2012. The commemorative hardback book Titian | Metamorphosis: Art Music Dance immortalizes the Royal Ballet-National Gallery collaboration in 180-plus pages of thought-provoking interviews and stunning photographs. The book gives us insight into some enduring tensions in art and dance: that between past and present, power and vulnerability, narration and abstraction, and technology and tradition.

This volume is itself a work of art, edited by Dr Minna Moore Ede, Assistant Curator of Renaissance Paintings at the National Gallery. Photographs by Gautier Deblonde, Johan Persson, and Andrej Uspenski decorate every page. Ede’s conversations with three contemporary British artists (Mark Wallinger, Conrad Shawcross, and Chris Ofili) make up the text in Titian | Metamorphosis. Together, the text and images reveal the project’s progress from nascence to maturity in a vivid and uncluttered package.

Each artist was commissioned to create work for the National Gallery, and was separately teamed up with a composer and choreographers to design a ballet. Wallinger created the ballet Trespass with composer Mark-Anthony Turnage and choreographers Alastair Marriott and Christopher Wheeldon. Shawcross’s Machina featured music by Nico Muhly and choreography by Wayne McGregor and Kim Brandstrup. Ofili’s designs for Diana and Acteon set the stage for choreography by Liam Scarlett, Will Tuckett, and Jonathan Watkins. Composer Jonathan Dove and librettist Alastair Middleton rounded out Ofili’s team.

Metamorphosis: Titian 2012 was conceived by Ede and former Royal Ballet Artistic Director Monica Mason. Their intent was to generate new ballets and new works of art in response to three Titian paintings (Diana and Callisto, Diana and Actaeon, and The Death of Actaeon) on exhibit at the National Gallery. Ede began planning the exhibit with Diaghilev in mind, aiming for the sort of “total artwork which was…at the cutting edge of every artistic discipline” produced by the Ballets Russes in the early twentieth century.

“Cutting edge” is one way to describe Shawcross’s mammoth robot in the ballet Machina. By all accounts it was one of the greatest challenges of the project, and by some accounts it was unsuccessful as a stage set. In terms of narrative, Shawcross chose to continue the story Titian laid out in The Death of Actaeon, calling Trophy, his gallery piece, “a post-mortem on Actaeon’s death.” The potential threat of technology is an idea Shawcross explored in both works, and one he describes as a personal struggle in his creative process.

Wallinger toyed with a different kind of edge in his works, Trespass and Diana. His was a question of limits: how far is too far to tread into off-limits territory, be it personal space or outer space? Both of his creations played with watching and being watched, an idea Titian addressed in the painting Diana and Actaeon. Diana, Wallinger’s exhibition piece, was a fully functioning bathroom (complete with naked woman) into which gallery-goers could peep through any of four apertures. Trespass was partly inspired by the lunar landings and presents themes of reverence for the unknown and touching the untouchable. Some critics have argued that this entire project did just that to Titian—that it trespassed in restricted territory and in some way defiled or insulted Titian’s eminence.

Ede makes it clear that her motivation was reverence; Titian 2012 was to be “a project that would celebrate the greatness of these paintings, reminding us of their ongoing importance by commissioning contemporary responses.” In all three interviews, the level of respect and excitement Ede and the artists have surrounding the three Titian paintings is unmistakable.

Titian was not only a virtuoso painter but a master storyteller, something that, according to Ede, is rare in the work of contemporary painters. Monica Mason charged Ofili’s team specifically with creating an explicitly narrative ballet, something that until very recently most choreographers wouldn’t touch. Reading through the book, it was interesting to note how broadly the artists interpreted the idea of “narrative.”

Ede’s conversation with Wallinger focuses on ideas that should resonate strongly with performers: those of watching and being watched, and how men see or portray women. (Alastair Marriott expands on that here, noting that historically, it’s “a man who creates the image of a woman.”). Fittingly, then, the many images of Diana in this project—from live woman to industrial machine and various semi-abstractions in between—were created by fourteen men.

Chris Ofili describes how getting in touch with Ovid’s epic poem Metamorphosis (also Titian’s source material for the paintings) allowed him to feel included in the ongoing, ever-changing process of storytelling, rather than “relegated to the position of pure admiration.” Titian | Metamorphosis gives readers that gift by granting us access to the artists’ working process. Through words and images, we too become part of the dialogue surrounding the perennially provocative questions of power and precedence.

Titian | Metamorphosis: Art Music Dance

Art Books and the Royal Opera House, 2013