by Emily Kate Long

You stand on a dimly lit stage. The murmur of the audience on the other side of the curtain swells and then settles. The music starts, the curtain rises, the lights go up…and suddenly you feel completely disoriented, like you’re on a different planet. You’re blinded from the sides by brightly colored light. In front of you, the darkness seems endless. Where are the walls? How far away is the floor? Are you even standing straight? How are you supposed to dance when you can’t tell which way is up?

You stand on a dimly lit stage. The murmur of the audience on the other side of the curtain swells and then settles. The music starts, the curtain rises, the lights go up…and suddenly you feel completely disoriented, like you’re on a different planet. You’re blinded from the sides by brightly colored light. In front of you, the darkness seems endless. Where are the walls? How far away is the floor? Are you even standing straight? How are you supposed to dance when you can’t tell which way is up?

No dancer wants to be caught in such circumstances. If this scenario is familiar to you, your balance organs and proprioceptive sense may need a tune-up. For this installment of Finding Balance, I’m going literal and taking a look at the relationship of balance, proprioception, and alignment onstage and in the studio.

In her book Dance Mind and Body, Sandra Cerny Minton defines balance as “a body feeling of being poised or in a state of equilbrium. If you are balanced, you are centered and will not fall by giving in to the force of gravity.” The International Association of Dance Medicine and Science (IADMS) tells us that proprioception is the physical sense or feeling of your moving body. Sometimes it’s nicknamed the “sixth sense.” In a very simple way, you could think of balance as the feeling of the still self, and proprioception as the feeling of the moving self.

In the scientific sense, balance happens when an object’s center of gravity is placed over its base of support. A larger support base and lower center of gravity equal more effortless balance. To illustrate, think of the ease of balancing barefoot in a second-position grand plie with the hands on the hips and eyes looking straight ahead—wide base and low, compact center. Now contrast that with a balance on pointe in a back attitude with asymmetrical arms and a turned and inclined head—small base, high center, plus a lot of extended limbs to complicate things.

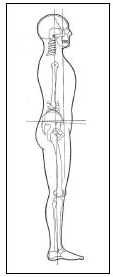

Another concept to consider in the discussion of balance is alignment. Correct static alignment is the stance featuring left-right symmetry in the body from a front or back view, with a vertical line passing through the earlobe, shoulder joint, trochanter head, kneecap, and the front of the ankle joint from a side view. Dynamic alignment refers to the body’s parts relating to one another in a balanced way when the body is in motion. Good alignment is inherently balanced. Essentially, it’s good biomechanics. You could say that proprioception is the feeling of one’s dynamic alignment. (Interestingly, these two alignment terns are also commonly used in mechanical engineering. I love the paradox that we can only appear to transcend the laws of physics by adhering to them!)

One last idea we’ll look at is centeredness, both as a physical feeling and a mental image. Centering is equally physical and psychological, according to Minton. Bodies have a center of gravity (located in the pelvis) and a center of balance (the solar plexus) and the relationship of these two physical centers affects balance. Minton’s defnintion of psychological center is roughly akin to the IADMS definition of proproiception: a mental awareness of what the body is doing as it moves. The key difference is the confidence aspect of being mentally centered. Minton notes that “skill in balancing is tied to the less concrete concept of body awareness and the psychological aspects of center…Body awareness involves having an accurate sense of where you are moving in space and what parts of your body are moving.”

So, it seems that we have a feedback loop going on here…proprioception contributes to feelings of being centered or aligned, which affect balance, which gives us feedback about how our body is in space. In this way we move in and through space, continually processing sensory feedback and making adjustments.

Ensuing the accuracy of all this information is important for several reasons. Not only does good alignment keep dancers safe, it contributes to the artistic experience. In writing for IADMS, Sally Radell calls proprioception “a critical ingredient to being a technically skilled, aware, and expressive dancer.” Accurate proprioception reduces a dancer’s reliance on the mirror to learn and correct movements. Feeling more comfortable onstage makes the audience more comfortable and involved, contributing to the illusion of naturalness or reality we aim to create in performance. By maintaining the integrity of our sensory feedback loop, we become better technicians, better artists, and enable ourselves to dance longer.

Back to that curtain rising. Why is it so easy to become disoriented onstage? Why do some balances keep falling apart no matter how hard we try? Somewhere in the loop, there’s a piece of missing or inaccurate information. How does one go about finding and correcting the error? This is where the detective work starts. The hard part is that there are a lot of factors involved. The good news is that since they’re all related, there’s no wrong place to begin your investigation. Best of all, feelings of balance and proprioception are always evolving, and tuning into them is a truly fun and rewarding challenge.

Back to that curtain rising. Why is it so easy to become disoriented onstage? Why do some balances keep falling apart no matter how hard we try? Somewhere in the loop, there’s a piece of missing or inaccurate information. How does one go about finding and correcting the error? This is where the detective work starts. The hard part is that there are a lot of factors involved. The good news is that since they’re all related, there’s no wrong place to begin your investigation. Best of all, feelings of balance and proprioception are always evolving, and tuning into them is a truly fun and rewarding challenge.

Dancers face some common obstacles in assessing alignment and balance. One is muscle memory. Habitual movement and alignment patterns can feel right even when they’re faulty. Because faulty alignment will feel normal eventually, testing balance in unusual or playful ways can lead to surprising insights about one’s balance or alignment deficits.

Another obstacle is bridging the gap between what good alignment looks like and what it feels like. Most ballet studios have at least one mirrored wall, so most ballet dancers learn using the mirror from a young age. The mirror can be both a useful tool and a handicap. We come to rely on it and relate to it in very specific and personal ways as we learn and practice movement. The mirror is necessary to re-train alignment, but the work can’t stop there. The new neuromuscular patterns must then be internalized so they show up when we start moving. For that reason, I think it’s best to do alignment work outside of class to avoid reinforcing a pattern of reliance on the mirror.

A third challenge to balance is the drastic difference between the sensory input we get in the studio and the input we get onstage. Costumes, lights, sets, and stage makeup replace leotards, mirrors, solid walls, and familiar faces. The surprise of a new environment can really shake up a dancer, no matter how experienced. Sensory overload is very difficult to ignore.

One last challenge is compensation from injury. I won’t go into much detail here, because I haven’t experienced any serious acute injuries. I will say that in my career experience so far, my pain level has been closely linked to the integrity of my alignment and my proprioceptive acuity. For me, persistent or recurring pain has become a red flag that something’s up and I need to “get out of the mirror” and figure out what’s going on with my sense of alignment or tension level.

So, where to start? The eyes, the balance organs in the inner ear, and the reflexes of the muscles contribute to steadiness and balance, and therefore to the accuracy of our proprioception. By handicapping balance with removal of a sense, we can train all of its helpers to become more skilled and adaptive. This is beneficial when our environment changes, as on stage. It also increases awareness of the body’s own patterns and tendencies, helping to keep us injury-free.

One place to begin an assessment of balance and alignment is with this simple test. How long can you stand on one leg with your eyes closed? Thirty seconds? Less? More? What about the other leg? What happened in your body when you began to lose your balance? Did you become tense or hold your breath? Open your eyes and check your alignment. Close them and test yourself again.

Once you’re steady on one leg with closed eyes, you can experiment with surfaces that are less stable than the floor. The world is your oyster here: pillows or cushions, a rolled towel or yoga mat, BOSU trainer, or wobble board present greater challenges for your balance. The more stuff you can stand on, the better.

An exercise I really like (adapted from Eric Franklin’s book Conditioning for Dance) is to stand on two feet on the BOSU with my hands folded behind my head. With eyes closed, I do a few plies to get a sense of what’s going on in my body this particular day. With eyes open, I begin to round my spine forward and backward, gradually increasing range of motion as I feel more stable. It’s amazing how sturdy and grounded I feel once I have two feet on the floor again. Standing or hopping on one leg in the pool with open or closed eyes is also a fun test…just not too close to the deep end!

Franklin makes an important point about muscular tension as it relates to stability. In general, “stability is not achieved through restricting movement but by efficient balance of forces.” So, more muscle tension does not equal better balance. He offers a more specific example: “…tension in the diaphragm can trigger a tight neck, possibly causing you to hold the shoulders higher than necessary, elevating the center of gravity.” Recall that a higher center of gravity presents a greater challenge to balance. In other words, when you’re retraining balance and alignment, it’s important to stay relaxed, both physically and mentally.

Franklin makes an important point about muscular tension as it relates to stability. In general, “stability is not achieved through restricting movement but by efficient balance of forces.” So, more muscle tension does not equal better balance. He offers a more specific example: “…tension in the diaphragm can trigger a tight neck, possibly causing you to hold the shoulders higher than necessary, elevating the center of gravity.” Recall that a higher center of gravity presents a greater challenge to balance. In other words, when you’re retraining balance and alignment, it’s important to stay relaxed, both physically and mentally.

This is where the mirror can cause problems for dancers. Our reflections in the mirror can conjure up all sorts of feelings and distractions. Many of these feelings can cause tension in the body, damaging our balance without us even realizing it. Tension, stress and fear cause opposing muscle groups to restrict one another, and as Franklin tells us, restriction of movement works against stability.

Say you’ve been practicing balance with your eyes closed and checking your alignment with the mirror as part of your cross training. What happens when you get back into the studio? You don’t want to rely on the mirror. The more we train our feeling of balance, the more we can trust ourselves, and the less we will feel like we need the mirror. The less we rely on it, the less significant it becomes, and the less power it has to cause tension.

Another trouble with a frontal mirror is that it can bring about a disproportionate awareness of alignment en face at the expense of real proprioception and a sense of moving alignment. Re-orienting one’s physical relationship with the dance space through mental imagery can help restore a more three-dimensional sense of alignment. Is the body aligned with the ceiling? The floor? The back of the room? What if there were mirrors everywhere, or no mirror? Additionally, it can help to visualize the corners of one’s personal space as planes rather than points to tune the body into the direction one is facing. Franklin also offers some helpful images for the eyes that can be used when the body is still or in motion. Imagine that the eyes are a spotlight. Do they cast light where you want them to? If the face is one huge eye, what will it see as its gaze sweeps over the space? What if there are eyes on other parts of your body? What do they see?

Balance can be so elusive and so frustrating, but it doesn’t have to be that way. The more we test and play and imagine, the better our bodies will work hard for us when we need them to. I hope some of the information here will be a useful starting point for readers interested in exploring the limits and possibilities of balance. If you’re looking for more, here are a few other online sources to check out:

“Mirrors in the Dance Class: Help or Hindrance?” http://www.iadms.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=400

“Dynamic Alignment, Performance Enhancement, and the Demi-Plie”

http://www.iadms.org/associations/2991/files/info/Bulletin_for_Teachers_1-2_pp8-10_Lewton-Brain.pdf

“Proprioception”

http://www.iadms.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=210

…And some books:

Physics and the Art of Dance by Dr Kenneth Laws

Conditioning for Dance by Eric Franklin

Dance Mind and Body by Sandra Czerny Minton

As far as the routine work of class and rehearsal is concerned, dancers’ bodies are a little different every day, so our sense of ourselves has to be fluid and quick to re-calibrate. Part of what playing with balance and body awareness has taught me—maybe the most important part—is to be more comfortable with being uncomfortable onstage, knowing that I’ve trained my senses to work for me if I just let them do their job. That training gives me tools to push my physical and expressive limits further and further. Some of the onstage disorientation never goes away, nor should it. It’s what makes a performance so exciting and special. Which is where we left off…

You stand on a dimly lit stage. The murmur of the audience on the other side of the curtain swells and then settles. The music starts, the curtain rises, the lights go up…now what happens?

Assistant Editor Emily Kate Long began her dance education in South Bend, Indiana, with Kimmary Williams and Jacob Rice, and graduated in 2007 from Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School’s Schenley Program. She has spent summers studying at Ballet Chicago, Pittsburgh Youth Ballet, Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School, Miami City Ballet, and Saratoga Summer Dance Intensive/Vail Valley Dance Intensive, where she served as Program Assistant. Ms Long attended Milwaukee Ballet School’s Summer Intensive on scholarship before being invited to join Milwaukee Ballet II in 2007.

Ms Long has been a member of Ballet Quad Cities since 2009. She has danced featured roles in Deanna Carter’s Ash to Glass and Dracula, participated in the company’s 2010 tour to New York City, and most recently performed principal roles in Courtney Lyon’s Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, and Cinderella. She is also on the faculty of Ballet Quad Cities School of Dance, where she teaches ballet, pointe, and repertoire classes.