by Allan Greene

PART THE FIRST

This is going to be a personal reading of the White Swan score. How could it be otherwise? I am going to lead the reader through a walking tour of my thoughts as I try to explain the method in the un-methodical: the search for a way to convey through musical sounds the score’s layered and sometimes contradictory messages.

Here’s what we’re dealing with: the historical context of the music, the dramatic role of the music in the context of the larger story, the meaning of the orchestration, the various “personalities” embodied in the score, and of course this correspondent as the particular messenger of this reading.

Undina came first

It makes sense, when you think about it, that Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was smitten with opera. Which of Tchaikovsky’s works do you know? The ballets, the first piano concerto, the 1812 Overture, Romeo & Juliet (at least the soaring love theme), probably the Serenade for Strings, possibly one or more of the last three symphonies. What unites all these works? Their vivid melodrama.

What you may not know, and most listeners don’t, is that Tchaikovsky wrote eleven operas, from Voyevoda at the beginning of his career (1869) to Iolanta the year (1892) before his death. He loved stories and was apparently a great storyteller. From his early youth he was always very literary, a voracious reader. He became a hyper-prolific writer of concert reviews and letters.

He developed into an exceptionally emotional adult. Even leaving his emotional life out of it, his mature aesthetic orientation was nervous and super-charged.

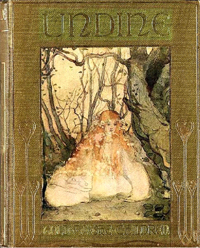

After his modest success with his first opera, Voyevoda, he turned to a more mythical but tragic romance based on a popular 1811 literary fairy tale, Undine, written by the German novelist Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. Tchaikovsky’s Undina (1869) never made it onto the stage. Indeed, Tchaikovsky was given to bouts of self-doubt and depression, and, after Undina had been rejected by the Imperial Theater, he took it out on the manuscript, destroying the most of it.

But we are in the fortunate position in 2012 to be able to listen to what escaped the flames. For example, consider this love duet from the final act:

Did you listen to the music? Pretty powerful stuff from the hand of the twenty-nine-year-old composer. One wonders how much of the rest of Undina was this intense.

Oh, and one other thing you may have noticed: that this duet is nearly identical to the music for the White Swan Pas de Deux. Possibly the most important moment in classical ballet was re-manufactured from the radio echo of an early German romance. One wonders whether this fact is of critical importance, or whether it is only a time-saver to speed up the composition of an evening-length ballet.

It couldn’t have been that much of a time-saver, because it had to be expanded, re-orchestrated and given a long introductory harp solo and a coda, both of which required transitional passages. My suspicion is that Tchaikovsky concluded that the aesthetics and the psychology of the Undine made a pretty good match with the Swan Lake scene.

What does this have to do with Jungian psychology and artistic expression, you may ask. Recall that I suggested in last month’s column that musical works can have, at minimum metaphorically, individual or multiple personalities, and that the interactive behaviors of these personalities can drive a dynamic appreciation of the piece’s impact.

The operatic duet, while appropriately exciting and touched with the Tchaikovsky genius for melody, is similar to many other tragic love duets in the Romantic period. What was it about this material that convinced him that it could be transferred from ill-fated water sprite to (in the original version) ill-fated swan queen?

Here we have to dig into the actual music. This will entail a bit of imagination as we characterize sections of and materials in the score.

The Score: Form and Content

In conventional musical analysis, which I’d like to refer to as Music Theory (because that’s what everyone else does), the word “form” refers to the structure of the music as made up of so many sections. When we say a Chopin mazurka has an A-B-A form, we mean that the first section has one kind of sound with a particular melody and particular harmonies, that the second section has a different melody and harmonic scheme, and that the third section is a repetition or near-repetition of the first section.

The Undina duet has this form: A-B-C-B-A1, where the last segment (in which Undina and Huldebrand sing together) is both a repetition and a slight alteration of the first section.

The Swan Lake pas d’action has this form: Introduction-A-B-C-B-C-B-A1+2-E, where E is the Coda. The letters in Swan Lake correspond to the similar sections in Undine, although the C sections are largely different from one another. (I’m analyzing the 1880 version of Swan Lake, as Tchaikovsky would have heard it. The 1895 version that is more commonly performed is from after Tchaikovsky’s death (1893), and so wouldn’t have reflected his intentions.)

Now that we’ve mapped out just how the score was expanded, we can look at it section by section. (The recording we will be referencing is Swan Lake: Act II, No. 13, Yehudi Menuhin, violin, Philharmonia Orchestra, Efrem Kurtz, conductor, © 2011 Past Classics.)

Introduction: What’s up with the Harp? http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 0:00-0:56

The harp family is one of the more ancient musical instrument groups. According to the website of The International Harp Museum in Orlando, “The harp is one of the oldest musical instruments in the world. The earliest harps were developed from the hunting bow. The wall paintings of ancient Egyptian tombs dating from as early as 3000 B.C. show an instrument that closely resembles the hunter’s bow, without the pillar that we find in modern harps.” In Western art they’re associated with the out-of-doors; this is true perhaps because their timbre evokes nature sounds, gentle breezes, rustling leaves and rain.

The Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, Russia boasted of having an unusually fine harpist, Albert Zabel. Drigo, Pugni and Glazunov scored conspicuous solos for Mr. Zabel in their ballets, although the most memorable were created for him by Tchaikovsky. Tchaikovsky could guarantee a coup de théâtre with a florid cadenza for Mr. Zabel. And that’s how the feminine sound of the harp, propagating waves of notes across the footlights, came to be associated with the prince, the cattails and the marshes of the lake of swans.

Section A: An Italianate notturno http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 0:57-02:33

Tchaikovsky traveled widely in Western Europe, and, although he affirmed his favorite city was Paris, he had a special affinity for the sunny culture of Italy. Rossini’s operas were among his favorites, and he judged Mozart’s Don Giovanni to be the greatest opera of all. For many artists, Italy was the coming-together of many crucial strands: Classicism, natural beauty, Renaissance ideals, humanism, color and sun, the elusive balance between the mind and the body.

One of the classic Commedia dell’Arte set-pieces was the moonlit lover singing to his beloved, stereotypically accompanied on the lute or mandolin. Listen to the music at the beginning of Odette’s adagio: the plucked strings (harp), then the lover’s plangent voice above it (solo violin). Although in its original setting, Undina’s and Huldebrand’s “O happiness, O blessed moment”, foreshadows a tragic death, in Swan Lake it places us emotionally where masculine yearning wishes through sheer force of art to melt feminine diffidence. One can only imagine the complex personal history that Tchaikovsky sought to communicate through this moment.

Section B: Pulsating Woodwinds 1 http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 2:33-3:02

The nine bars of pulsating, staccato woodwinds is a vocal accompaniment in Undina. In Swan Lake there is no intensifying soprano line, so it takes on instead a strange out-of-context character. It is a true invention, an amalgam of several things: it’s a folk dance, with the tiny tessitura and rote repetition of the un-schooled musician; it’s a pizzicato ear-worm in a triple meter, unfolding too slowly to have happened in the natural world, but instead sursurrating at the decelerated pulse of Tchaikovsky’s purple imagination; and it sets up aesthetically the “Peasant Pas” that follows.

Section C: The “Peasant Pas” 1 http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 3:02-3:49

That’s what I call the next fourteen bars (and their near-repetition later in the music). Again, this is not just fish, nor just fowl (not even swan). It is a subtle blending of bright, academic figurations in the solo violin, and a lute imitation in the rest of the strings. If you could re-imagine the violin solo played twice as fast, it could be one of those elaborate Italian Baroque violin concerti that Bach managed to perfect. At Tchaikovsky’s speed, however, handcuffs are slipped on the glissando-like scales and ricochet bowing, in a way that perhaps inspired the choreographer to make the swan break away yet never escape. But I’ve said too much. The symbiosis between the music and the movement-drama will be discussed next month.

Section B: Pulsating Woodwinds 2 http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 3:49-4:19

There follows a repetition of the nine bars of throbbing winds, although pitched higher, which creates a sense of greater intensity without changing the basic pulse. This sets up an iteration of the “Peasant Pas”.

Section C: “Peasant Pas” 2 http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 4:19-4:39

Fourteen bars of the lack of escape velocity are telescoped into six bars. The yearning is becoming unbearable.

Section B: Pulsating Woodwinds 3 http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 4:39-4:51

This material is telescoped from nine bars in the two prior appearances to four bars here, and the melody is expressed as a simple ascending octave scale, no longer a repeated hummable major third. It creates a sense closure similar to the sense of closure in a classical concerto leading to the soloist’s cadenza (cf. the much longer comparative section in Tchaikovsky’s Third Piano Concerto, Opus 75, used by George Balanchine in Allegro Brillante).

Section A1: Cello Cadenza http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 4:51-5:02

Sure enough, there is a modest cadenza which introduces the solo cello. Just as Huldbrand, the knight, takes up Undina’s notturno melody, the cello (the personification of the prince) seizes the lead here, showing that the violin has been captured and tamed.

Section A1+2: Notturno Recapitulation (Duet) http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 5:02-6:39

In the recapitulation of the notturno serenade one finds the fully-realized expression of the sexual tension between the prince and the queen. The two melodies, the main theme in the cello and the counter-melody in the violin, track quite closely the original duet from Undina. Tchaikovsky plainly concluded that what’s sauce for the sprite is sauce for the gander. It’s interesting to note that in both Undina and Swan Lake this section resolves into a major chord, G-flat in Undina and E-flat (for the Coda) in Swan Lake. (The 1895 version, incidentally, returns to the Undina cadence.)

Section E: Coda (Original Version) http://youtu.be/Sl5Vuz9dkJU, 6:39-end

There are two versions of Swan Lake, the 1875-1876 original and the 1895 posthumous modification for Marius Petipa by Riccardo Drigo and Tchaikovsky’s younger brother Modest. Unfortunately, it’s the latter that is usually performed. There’s no way to know whether Tchaikovsky would have gone along with the changes realized in the posthumous version, so for the purpose of understanding what Tchaikovsky had in mind as he created the score, the 1895 version is useless.

That having been said, this beautiful coda, which was a contemporary ballet convention, appears to have had less importance to the psychological revelation of the protagonists and more importance as an opportunity for the dancers in those roles to show off. In that light, it wasn’t much different, functionally, from the harp solo that leads off the number.

Tune in tomorrow for the second part of this post…