by Emily Kate Long

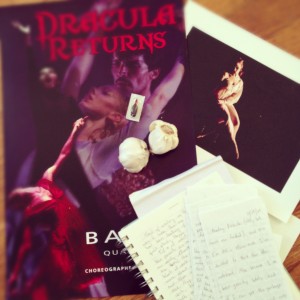

Last month I had the opportunity to return to the role of Mina Murray-Harker in Deanna Carter’s Dracula. It was the season opener for Ballet Quad Cities when I joined the company in 2009, and my experience then was radically different from now. The process of re-learning got me thinking about the dancer’s function in the existence of a role. To remember and pass on steps is one thing, but what about the aspect of characterization? We must preserve, but we must also advance. Interpretation and personalization are inherent in live art. How can we go about our work in a way respects the choreographer’s wishes?

Mina was the first real character role I ever danced, and Dracula was the first ballet I ever performed as a full member of a professional company. It was the beginning of my awareness of the huge clash between the academic, black-and-white (or, perhaps more appropriately, black-and-pink) framework I clung to as a student and the messy, splatter-colored, pick-your-own-adventure world of a professional career.

My professional performing experience up to that point had consisted largely of being the third-shortest girl in a line of umpteen in hundred-year-old tutu ballets. Conformity was the order of the day, and I quaked in my pointe shoes at the prospect of sticking out—being noticed usually meant you had done something wrong. We had a saying at Milwaukee Ballet among the trainees: “Know your role and shut your hole.” Great for staying out of trouble, not so great for artistic self-discovery.

I had anticipated that professional life would just be an extension of what I already knew: take class and do as I was told, learn choreography and do as I was told, perform choreography and hope I didn’t get reprimanded afterwards. Feedback or not, there was always the nagging question of whether my work had been good enough. Little did I know that being an artist has a lot more to do with being honest and generous and responsible than about being right by arbitrary standards.

The first time I danced Mina, my approach was to address the choreography for its own sake. I wanted (because then, I needed) to be told exactly what to do, step-by-step, count-by-count. I felt I should completely subject myself to the steps; it was my understanding that that was the only way to be a good dancer. The problem was that I was only looking at one set of information—the steps as they were given to me. I was ready to take information in, but I didn’t know what to do with it! A body and a brain can only do so many things at once, and certain physical actions are mutually exclusive, plain and simple. My extreme desire to please led to confusion and frustration when I tried to do too many things at once. I didn’t yet have enough experience to make responsible artistic choices, so I felt uncomfortable making any choices at all.

That eager but uninformed and highly self-conscious method prevented me from ever really discovering who Mina was as a character. Her relationship to herself and other characters meant very little to me in 2009 because I was paying so much attention to doing the right steps.

Fast forward to 2012. The new issue is balancing my sense of duty to the choreography with my desire to take artistic ownership of the role. I want to become Mina so that the audience can know her and sympathize with her story. However, I don’t believe a role ever truly belongs to the dancer. We simply foster and nurture it until it gets passed on to the audience and the next dancer who performs it. Our individual characterizations are born during the rehearsal process, and live and die over the course of the performance. That process itself presents a whole new conflict. To what extent is it a dancer’s business to interpret? What are we allowed to do with the information handed down to us? Where do we draw the line between being the instrument and being the artist? Only trust, communication, and the experience gained by trial-and-error can answer those questions.

Before, I had relied on specificity as a crutch. This time, I was able to use it as a tool for clarity, both physically and psychologically. I tend to let negative self-chatter get the better of me onstage, so I found it really helpful to give myself a strong mental script to follow. That meant thinking long and hard about having a reason for every action. Being comfortable with the basic blueprint of the ballet also gave me the opportunity to address finer technical details. It helped me take off a lot of the pressure I put on myself—knowing what I was trying to say made it easier to ad-lib when necessary and not get hung up when one step or the other wasn’t perfect. It also made it much easier to remember sequences of actions. It is amazing how much difference subtle things like timing of connecting steps, height of a partner’s hand, head angles, and speed of stage mime can make for dancers and audience alike.

It goes without saying that some choreographers are more open than others to collaboration. I think it’s essential for both dancers and choreographers to be clear on how open the choreography is to artistic interpretation by the dancer. Here, with this particular choreographer, in this ballet, and with this cast, I found a liberal approach to be appropriate. Where I had formerly assumed no permission, I now tested every idea I had until I found the most effective. Sticking my neck out was scary, but finding out where I could trust my own judgment and where I was still making less-than-ideal choices was worth it.

Assistant Editor Emily Kate Long began her dance education in South Bend, Indiana, with Kimmary Williams and Jacob Rice, and graduated in 2007 from Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School’s Schenley Program. She has spent summers studying at Ballet Chicago, Pittsburgh Youth Ballet, Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School, Miami City Ballet, and Saratoga Summer Dance Intensive/Vail Valley Dance Intensive, where she served as Program Assistant. Ms Long attended Milwaukee Ballet School’s Summer Intensive on scholarship before being invited to join Milwaukee Ballet II in 2007.

Ms Long has been a member of Ballet Quad Cities since 2009. She has danced featured roles in Deanna Carter’s Ash to Glass and Dracula, participated in the company’s 2010 tour to New York City, and most recently performed principal roles in Courtney Lyon’s Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, and Cinderella. She is also on the faculty of Ballet Quad Cities School of Dance, where she teaches ballet, pointe, and repertoire classes.