by Risa Gary Kaplowitz

Although it’s been nearly four decades, I remember like it was yesterday–standing in line with my friends at Lincoln Center by 7:30 AM to get standing room tickets to see Cynthia Gregory dance. She was an American Ballet Theatre superstar at the time, and no matter what she performed (but especially when partnered by Fernando Bujones), we were ravenous to dwell with her in the magical world she created onstage.

Ms. Gregory’s assured technique, especially her balances were legendary. Solid like a statue with a beating heart, she would take an attitude line en pointe and hold, hold, hold it as we held, held, held our breath only to exhale when an ever so slow extension into arabesque was complete. Then we exploded into rock-concert-fan-screams; a cacophony of bravas and oh-my-gawds.

Yet, as wonderful as these heart-stopping moments were, they never came at the expense of Ms. Gregory’s characterizations and musicality. Rather, she used her technique as a means by which to express whatever character she was portraying. She was a true ballet artist of the narrative ballets.

Unfortunately, in these days of what appear to be an Olympian approach to ballet, such ballet artists are hard to find. And sadly, many ballet schools and major companies do not seem to be doing enough to preserve ballet’s greatest asset—its ability to transcend words and transport an audience into their world. Ballet technique that explodes with meaning instead of fireworks is vastly lacking.

This is due in part to the thriving dance competition scene—one of the most prestigious is Youth America Grand Prix, which was featured in the recent movie First Position—and, more broadly, to the human nature of always wanting more. Many of today’s ballet students believe that the main goal of their training is to achieve higher extensions, bigger jumps, and more turns. As they obsessively view ballet wunderkinds on YouTube, ballet companies respond to the demand for ballet pyrotechnics by promoting hyper-technical dancers without much coaching on the subtleties necessary to make great art.

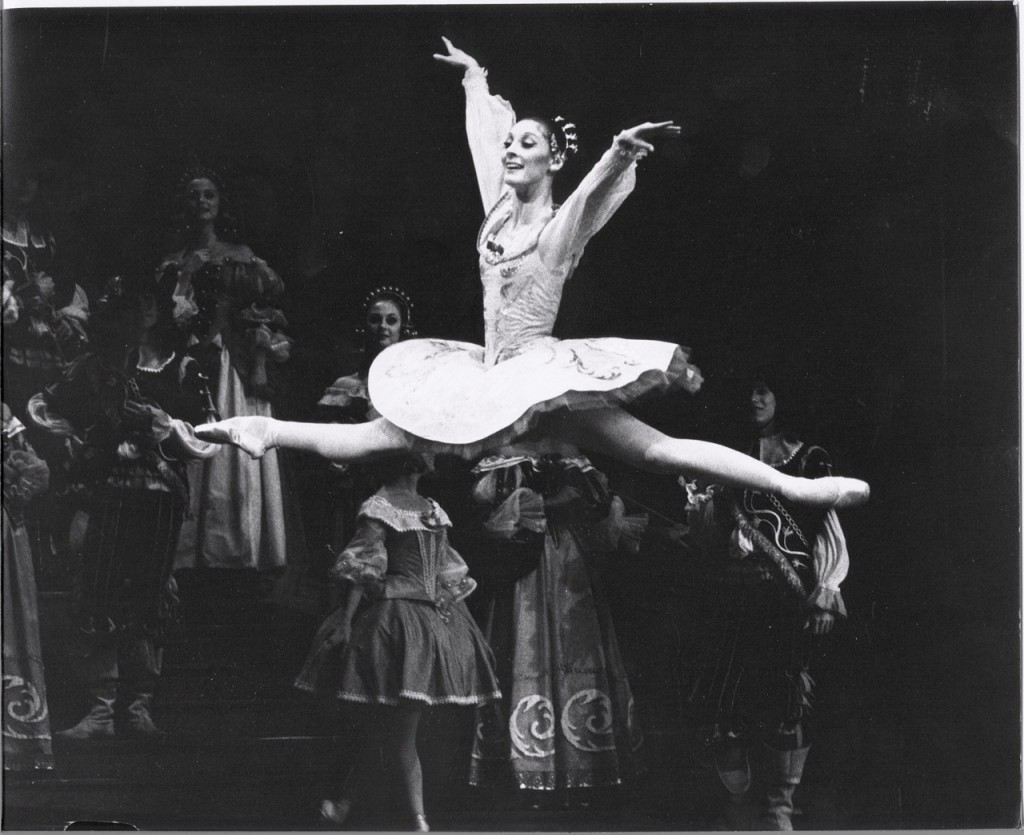

Thanks to YouTube, we can take a closer look into this dilemma. Below is a video of Ms. Gregory performing the Rose Adagio from The Sleeping Beauty in the late 1970’s. In it, she illustrates a ballerina artist who uses impeccable technique to provide a deep connection to her character, the sixteen year-old Princess Aurora. In the scene, Aurora is meeting her suitors for the first time.

Ms. Gregory’s portrayal clearly shows Aurora’s growth in both comfort and joy as she gains confidence dancing with her suitors. Ms. Gregory’s pitch perfect technique is in perfect harmony with the story and the music. Her nuanced gestures grow larger as Aurora’s confidence does. And, at the end, there is that arabesque extension— slow, controlled and deliberate. An enraptured ending to a demure beginning.

It is interesting to compare Ms. Gregory’s performance with that of the well-regarded Alina Cojocaru, a current principal with The Royal Ballet. Here, in a video of the same Rose Adagio filmed relatively recently, one sees a very capable ballerina with beautiful extensions, high retirés in her pirouettes, which is popular today (and something that I do love). Yet there is very little attention to showing the audience who she is and from where she came.

There is much to discuss in these two performances, but a few differences really stand out to me: First, with regards to the recurring motif of développés in à la seconde, Ms. Gregory’s initial partnered ones are modest and slow. As the dance continues, Aurora becomes more assured—her confidence grows and so too does that step in energy and abandonment.

Yet, Ms Cojocaru’s extensions in that same step begin high and bold. Since a dancer has only her body to tell a story, doing these high extensions with men whom she’s only just met strikes me as behaving less like a princess and more like the floozy in the kingdom. Where is the restraint necessary for the characterization and how can we be pulled into her world without it? Remember, the ballet takes place in the 19th century, which is when Marius Petipa choreographed it. A sixteen year-old princess sheltered by her parents due to Carabosse’s prickly curse would have not been nearly as worldly as a girl of that age today. Wouldn’t we appreciate those extensions so much more if she kept them more hidden until the appropriate time to let them fly at the end?

Second, with regards to the bourrée turns the ballerina does solo center stage, Ms. Gregory’s are born out of total bliss, each turn more gleeful than the next. Ms. Cojocaru’s on the other hand, end in static poses, which appear to be aimed more at showing off her lovely arched back rather than her happiness of an impending engagement. The bourrée’s themselves are aggressive, exaggerated, and fast—a quality more suggestive of the Black Swan rather than the over-protected young Aurora.

Finally, Ms. Cojocaru’s overall dancing in the video is spiked with an “Audience, look at me!” attitude and a bouncy anything-but-adagio quality. (Isn’t it called the Rose Adagio for a reason?). Ms. Gregory’s dancing, however, is for her suitors rather than for her fans.; her joy at being the young lady of the moment palpable. At the end, her Aurora remembers that she is supposed to have decorum and she returns to her initial restraint for her final bow to them. Ms. Cojocaru ends in a bow even lower than her suitors, which makes no sense to the story.

Ms. Cojocaru has many lovely characteristics. Her lines are gorgeous; her jump is light and high. I enjoy watching her. Yet, I am I am nostalgic for ballet artists like Ms. Gregory who made me forget that I was watching ballet steps. Certainly a great actress would not want me to focus on her diction.

I have had the honor of watching Ms. Gregory pass her artistic vision on to my school’s students when she coaches them during its summer intensive. The first question she asks each one is, “What is the story about and who is your character?”

Thinking deeply on these questions can make a very big difference in whether a dancer is an artist or merely a technician. Every single step must have meaning; every port de bras a gateway to the soul. In today’s world of increased technical prowess, imagine what ballet would be like if more coaches asked these important questions and most importantly, if more directors demanded the answers.

(For another recent article on Cynthia Gregory see this piece.)

Contributor Risa Gary Kaplowitz is a former principal dancer with Dayton Ballet and member of Houston Ballet and Manhattan Ballet. She has also performed with Pennsylvania Ballet and Metropolitan Opera Ballet and as a guest artist with many companies nationwide.

She was originally trained at Maryland Youth Ballet by Tensia Fonseca, Roy Gean, and Michelle Lees. She spent summers as a teen studying on scholarship at American Ballet Theater, Joffrey Ballet, Pennsylvania Ballet, and Houston Ballet. As a professional, her most influential teachers were Maggie Black, Marjorie Mussman, Stuart Sebastian, Lupe Serrano, Benjamin Harkarvy, and Ben Stevenson. She has performed the repertoire of many choreographers including Fredrick Ashton, George Balanchine, Ben Stevenson, Stuart Sebastian, Dermot Burke, Billy Wilson, and Marjorie Mussman.

After spending ten years in a successful business career while building a family, Risa returned to the dance world and founded Princeton Dance and Theater Studio (www.princetondance.com) and DanceVision, Inc. (www.dancevisionnj.org) with Susan Jaffe, former ABT principal ballerina. Risa is now PDT’s Director, and the Artistic Director of DanceVision Inc. Risa also founded D.A.N.C.E. (Dance As a Necessary Component of Education), an outreach program that brings dance to New Jersey schools.

Risa has choreographed more than twenty pieces, and her original full-length ballets, The Secret Garden and The Snow Queen, premiered with DanceVision Performance Company in 2008 and 2011, respectively. Additionally, she has choreographed for several New Jersey Symphony Orchestra family and school outreach concerts.

Risa is an ABT® Affiliate Teacher, who has successfully completed the ABT® Teacher Training Intensive in Primary through Level 7 and Partnering of the ABT® National Training Curriculum, and has successfully presented students for examinations.

She has lectured the ABT/NYU Master candidates on starting a dance studio. She is most grateful for her teachers who gave and (in the case of ABT® Curriculum) give her the exceptional tools necessary to have had a performance career and the opportunity to train others in authentically. She also feels fortunate to have had the opportunity to dance with and learn from many exceptional dancers.

Excellent article Risa. Thank you for so clearly articulating one of the most important issues in dance performance and training in ballet today. Roni Mahler, a colleague of Cynthia Gregory’s and soloist at ABT, was one of my mentors. She also stressed the importance of artistry along with excellent technique. I will be having my students read your article as part of their couserwork this year!

OK – Part 2 of my message after watching the vids – Musicality!!! Watching Cynthia Gregory dance, I felt the music in my body and remembered why I originally wanted to be a dancer. Watching Alina Cojocaru – she has beautiful technique, but as one of my teachers used to say – “why” – why are you lifting your leg here, why are you looking there, what are you trying to ‘communicate’ with that movement/gesture?

How can someone dancing so fully be boring – it is as you said in your article, there is no dynamic variation in her movement – it is all full out all the time. We teachers must demand artistry from our dancers.

Excellent points. Yes, a thousand times yes! Virtuosity should not be a substitute for character and story. Performance quality is often sacrificed for the Olympian aspect of dance, as you call it, and that’s a shame and a major loss for young dancers who need to learn how to express themselves on-stage, not merely execute steps. Should we blame shows like “So You Think You Can Dance”? lol….

There are points where I agree with you, bu SOMEONE has to play the devil’s advocate here. ;D

I do agree with your overall point that there needs to be some attention put towards maintaining artistic integrity and expression within athletic performers. (I know that’s a big generalization of everything you’re saying so that may not be EXACTLY what you’re getting at but…ya know)

But in Alina’s defense, you point out it’s ROSE’s adagio. and who is Rose?? Rose could be the character you’re describing: meeting her suitors in a demur way, growing with confidence as she dances. Or Rose might be a kind of show offy, floozy 16 year old princess. She’s excited about picking suitors and might be more than prepared to kick her leg up in front of the court to prove she’s a treasure worth fighting for.

You said it yourself, all us dancers have to communicate with is OUR body. So as we step in to unoriginal, handed-down roles and choreography, there will be differences in the way they’re performed. Alina’s Rose is a completely different person than Cynthia’s.

And YES. feel free to blame shows like “So You Think You Can Dance” because that’s a part of this generation. Our bodies are constantly pushed into a more flexible, stronger, sexier performing era and I think that change of times in itself is part of art.

Part of dance is the pursuit of perfection, an ever losing battle. …

Laura, Leigh and Just Me, you all bring up great points.

Laura, I would not only ask “why” but also remind my students that just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.

Leigh, Absolutely, shows like “So You Think You Can Dance” are big contributors to the problem. However, there are instances in that show when I have felt something deeper going on, especially pieces by Mia Michaels.

Just Me, yes, absolutely, each “artist” will be different. However, each artist needs to bring something to the stage besides gorgeous technique. I feel absolutely nothing watching Cojocaru….it is crass. One just has to read The Sleeping Beauty to know that she is intended to be a demure and lovely 16 year old. I do not agree with forming the story’s character into a dancer’s preferable way of moving. It should be the other way around. Ms. Cojocaru would still be able to pursue the role with her tones of brilliance…just not so blindingly brightly.

And Laura, I am honored that you would have your students read this as part of their coursework. I am just truly hoping that the tide will turn.

From my seat in a darkened theatre, I am SO tired of sloppy but numerous and super-fast pirouettes, jumps, and ballerinas who can put their feet behind their heads for no apparent reason. One single, beautiful, musical, heart felt turn is one of the most delicious things to watch ever. Just this last year I saw ABT perform Cunningham’s Duets and I was just amazed how glorious a simple tendu, grand plie in second, or a slow and luscious develope can be.

I’m really disappointed with how much is sacrificed for, as you say, the Olympics of ballet. Now I love technical brilliance, which I think is the foundation for great ballet, but technical pyrotechnics alone just set ballet up to become something that is not sustainable, unable to touch heart and soul, and loses it’s attachment to art becoming more aligned with sports.

~Lorry

Lorry, I completely agree with all that you wrote.

I am so tired of watching dancers and not feeling anything but impressed.

I am so glad that someone I know pasted a link to this page on facebook. I adored watching Cynthia Gregory it was beautiful. My personal preference is to more cabaret style dance before the classical, but seeing this reminded me of what classical can be like. As many of you say ballet and a lot of dance has just become Olympic style and as I can’t and won’t do that when my dancers perform against others they look different and sometimes “odd” yet I know that my dancers will love dance and not be put off because their legs aren’t as high as others rather they dance because they tell the story and feel it. Thank you for posting this article it has reminded that what I believe of dance is alive elsewhere and inspires me to keep with my messages.

I really enjoyed this post as this is something I often think about, particularly when I watch dance competitions. On one hand, I wonder how much of it for me is just nostalgia, and how much is well-founded concern. After all, the debate of bravura vs. artistry is a very old one. Still, I agree that dance is more than just athletics; it is an art. Therefore, the artistry is a must. Ballet should make you feel.

I have observed a lean toward the flashy in younger generations. I am an adult ballet student, and I currently take my classes with teens. At the school I attend, the curriculum is very specific, and in ballet there is not much emphasis on extreme athletics. My teacher often says she would rather see a beautiful arabesque at 45 degrees than one at 110 with no emotion. Unfortunately, I notice that when students leave for other schools, the most common reason seems to be that “we don’t do competitions” (or 15 pirouettes or huge “crotch-shot” jumps just to show we can). Luckily, these are still some students who appreciate the art, and hopefully audiences who do too.

If you do not mind, I think I will use this as a reading selection in my English class, as I work with students who are receiving performing arts training. Not only is it well-written, which will allow me to have them analyze craft, but it will also lend itself very well to debate since all of my students have either watched danced performances or performed themselves.

~ Elle

AdoreDance and Lisa, it’s always comforting to know that others feel the same way. Thanks for reading and commenting!