by Emily Kate Long

Last month’s “Finding Balance” explored the relationships among dancer identity, passion for dance, injury, and age. A month after writing that column, I can’t get away from the topic—it utterly fascinates and confounds me. I was directed by a friend to a widely cited study by Linda Hamilton (American Journal of Sports Medicine, March 1989) titled “Personality, Stress, and Injuries in Professional Ballet Dancers.” In it, Hamilton states:

“[The] dancer must possess extraordinary dedication, a limitless capacity for hard work, and the ability to persevere through more or less continual pain, in addition to having a specific body type and talent….[The] personality traits that are programmed into success in this profession may ultimately prove detrimental to those dancers who have not learned to work within the natural limitations of their bodies.”

The italicization of that last phrase is my own—is that the key to balance between doing our best and doing too much? How can we push ourselves hard enough that we achieve highly without letting those “success traits” run so rampant as to destroy us? How do we learn what our natural limitations are? How can we expand them?

Hamilton’s statement compelled me to seek out dancers I admire and view as highly self-driven, and ask them to weigh in on the subject of coping with and learning from injuries. Of those I contacted, three dancers were able to contribute to this article. My utmost thanks go out to them for taking the time to answer my questions candidly and thoughtfully.

Jeanette Hanley was a Leading Artist with Milwaukee Ballet when I was in the second company there. Her dancing and her spirit and her enthusiasm made a great impression on me—I never saw her get injured or upset, and her energy and motivation seemed endless. She was like superwoman, or the energizer bunny. She has since retired from dancing, but I still think of her as a role model. I decided to get in touch with her for this article to discover what strategies kept her going throughout her 21-year dancing career, and how she felt about retirement. She shared with me that her love of yoga and going to the gym made it easy to stay in good physical shape during layoffs, and that she never had trouble with injuries while she was dancing. With the birth of her daughter, healthy diet and exercise got her going again. Now that she’s retired, it has been helpful to have a new line of work that she loves. Always learning, Jeanette also takes karate with her daughter, and they will both be receiving black belts in the fall.

Katie Rideout and I attended Milwaukee Ballet School’s summer intensive in 2007 and spent two years together in Milwaukee Ballet II, 2007-2009. Katie has struggled with lower leg injuries as long as I’ve known her. In November 2011, after dealing with intense pain in her tibia for almost two years, she made the choice to take a break from dancing and finish her Bachelor’s degree from Point Park University. She later found out she had been dancing on two stress fractures. During her recovery period she struggled most with making decisions independently of a career-oriented framework. Addressing the reality of her injury –its severity was a direct result of overuse and denial—forced Katie to begin freeing herself from obsessive passion for dance in order to return to dancing and avoid re-injury. This, in turn, allowed her to establish new training habits: integration of Pilates work and a focus on technical efficiency rather than an exclusively aesthetic aim. Finishing her undergraduate degree also gave her another aspect of her person to cultivate: an understanding and exercise of her intellect, measured separately from dance achievements.

My good friend Jason Wang tore his Achilles’ tendon on August 30, 2011 and underwent surgery to repair it three days later. Naturally a planner, he, like Katie, found one of the greatest challenges in his recovery to be the uncertain timeframe and absence of a familiar “roadmap” in his decision-making process. The stillness that was necessary while waiting for doctors’ orders quickly degraded to depression; Jason felt he had been “stripped from [his] lifestyle without [his] own consent.” Also significant for Jason was the difference in coping with this long-term injury versus the short-term ones he had previously sustained: “…sitting and watching dancers do what I loved for weeks on end made me extremely stressed and depressed….[If] you’re not clear and sound in your mind then your physical side will become its collateral.” He felt it was important to step back and take time to clear his mind before deciding how to approach re-entry into the dance world.

I consider Jason, Katie, and Jeanette all to be high achievers. Pushing themselves to the limit and beyond just seems like a natural thing for them. However, in Katie’s case, pushing led to chronic injury. In Jason’s case, his inability to work led to feelings of uncertainty, depression, and isolation. Jeanette, however, was able to push herself through a two-decade career without major setbacks caused by injury. What’s her secret?

Could it be than Jeanette is simply older and wiser?

I recall another of Milwaukee Ballet’s leading artists telling me once that the time she spent in Boston Ballet II was the hardest of her life. Perhaps the more time we spend with ourselves, and the more adversity we face, the more we can come to understand that one of the “natural limitations of [our] bodies” is our very own psyche.

Readers, what dance-related experiences have forced you to face your inner demons and come out on top?

Contributor Emily Kate Long began her dance education in South Bend, Indiana, with Kimmary Williams and Jacob Rice and graduated in 2007 from Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School’s Schenley Program. Ms Long attended Milwaukee Ballet School’s Summer Intensive on scholarship before being invited to join Milwaukee Ballet II in 2007. She also has spent summers studying at Saratoga Summer Dance Intensive, Miami City Ballet, Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School, Pittsburgh Youth Ballet, and Ballet Chicago.

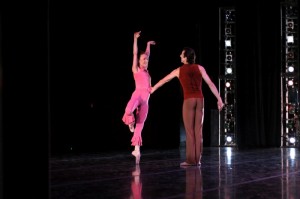

Ms Long has been a member of Ballet Quad Cities since 2009. She has danced featured roles in Deanna Carter’s Ash to Glass and Dracula, participated in the company’s 2010 tour to New York City, and most recently performed the title role in Courtney Lyon’s Cinderella and the role of Clara in The Nutcracker. Prior to joining Ballet Quad Cities Ms Long performed with Milwaukee Ballet and MBII in Michael Pink’s The Nutcracker and Candide Overture, Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty and La Bayadére, Balanchine’s Who Cares?, Bournonville’s Flower Festival in Genzano and Napoli, and original contemporary and neoclassical works by Tom Teague, Denis Malinkine, Rolando Yanes, and Petr Zaharadnicek.

This is an ongoing discussion I have with friends and students all the time. I think when we feel like dance has been stolen from us, whether through acute injury or sudden illness, we don’t accept our natural limitations of age and ability. That’s what I see among friends who refuse to accept getting older – they push too hard and continually injure themselves. But when you feel like this is a slow progression, it seems easier to accept and to work within your new boundaries. I find my abilities to do battu, or grand allegro, to be lessened – some days they’re good, sometimes not – but my abilities in other areas of dance increase – e.g. adagio. You have to rewrite your own dance agenda every day, no matter your age.

Thanks for the comment, Leigh. On the subject of feeling like dance is being stolen–when teachers ask us to change our technique, that same false sense of possession can take over and impede progress. your thoughts/experiences with this? I find it such a hard struggle that as much as we invest ourselves in this art form, we can never own it or possess it because it’s so much larger than us!