by Allan Greene

Let me get this out right up front: if you go for Arvo Pärt, you’ll love the late works of Franz Liszt.

I’ve played and loved the late Liszt since I was kid. It was in the late Sixties on a trip into Manhattan to the old Schirmer’s that I found a newly published Schirmer number called The Late Liszt. I was thirteen or fourteen and I had been composing atonal music for a few years; but as a piano student, Liszt, the Romantic, was my god. After going to considerable trouble to master his Liebestraum No. 3, I was taken by surprise that late in his life Liszt had composed these spare, non-bravura morceaux. That some were nearly atonal, un-moored from traditional harmony, made me even gladder.

I’ve played and loved the late Liszt since I was kid. It was in the late Sixties on a trip into Manhattan to the old Schirmer’s that I found a newly published Schirmer number called The Late Liszt. I was thirteen or fourteen and I had been composing atonal music for a few years; but as a piano student, Liszt, the Romantic, was my god. After going to considerable trouble to master his Liebestraum No. 3, I was taken by surprise that late in his life Liszt had composed these spare, non-bravura morceaux. That some were nearly atonal, un-moored from traditional harmony, made me even gladder.

All these years I’ve accompanied dance I’ve used pieces from that collection in classes. I have never, with one unhappy exception (Sir Frederick Ashton’s Mayerling), seen choreography to this music. This volume held, and holds, such meaning for me, its contents might almost be my autobiography. I’ve been troubled me all these years that I haven’t seen great dances to this profound music.

And then, while researching a column on Arvo Pärt, who is wildly popular with choreographers, it hit me.

Late Liszt is late Pärt. I mean, really.

Do they have a spooky, supernatural, counter-intuitive relationship, filled with seemingly strange coincidences? Let’s see. Liszt was Hungarian, Pärt is Estonian. Their native tongues are both members of the the Finno-Ugric language group. Both had an affinity for the avant-garde from the very beginning. Both suffered mid-career life changes that sent them into a quasi-religious bout of self-examination.

Except for the “dark night of the soul” that each went through, the coincidences don’t prove much. Liszt was a very public figure who set the People Magazine standard for celebrity and scandale in his day; Pärt is a private person, thrust into the public eye by his success translating his privacy into music. He has a stable home-life and a happy family.

But it is extraordinarily interesting to me these two composers more than a century removed from one another cross paths at a very particular point in their artistic journeys, after having gone through depression and soul-searching. The fact that Pärt has become so popular among choreographers and Liszt is not tells me something is wrong.

I’m going to right that wrong.

Initially, I’d like to suggest that Pärt may have led us to the edge of an age of Radical Diatonicism, much as Liszt blazed a path to radical chromaticism 150 years ago.

Diatonic versus Chromatic

It is a bit easier to follow my thesis if we understand the historic relationship between the diatonic (white-key) scale and the chromatic (all the keys on the piano) scale.

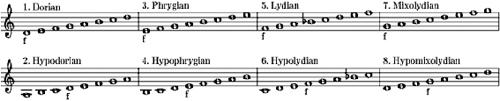

The diatonic scale held absolute power in Western music at least as far back as the 12th Century, when the earliest surviving notated music, that of the monk Perotin, was composed. Music was organized around seven tones, what we today call A, B, C, D, E, F and G. Music was characterized based on which of those seven tones dominated the melody. Depending on which tone it was, the music had a certain sound, called a mode (modus). What we today call a major scale was called the Lydian Mode. What we today call the minor scale (or natural minor scale) was called the Hypodorian (or Aeolian) Mode. There were eight modes, the most dissonant being the Phrygian and Hypophrygian or Lochrian.

In the Renaissance musicians and scientists began to appreciate that these modes could be expressed in any frame of reference, from the lowest note on a bass viol to the highest note on a sopranino recorder. They began to rationalize this relativity by inventing the twelve-note scale, which on the organ keyboard was organized as seven white keys and five black keys; and the black keys were called “accidentals”. In those days, tuning instruments was done differently, and different keys (like D major or B-flat major) had very definite moods. Andreas Werkmeister around 1690 suggested that any of the twelve notes could be the fundamental musical tone (the “f” in Illustration 1), an idea whose validity was finally demonstrated by Bach in 48 preludes and fugues in the twelve major and twelve minor scales which he called The Well-Tempered Clavier (i.e., the evenly-tuned keyboard).

Bach’s point of view gradually overtook the ancient modal aesthetic, and by the 19th Century the early Romantics (among them the greatest pianists of the epoch, Chopin and Liszt) were brazenly expanding the poetic language of music by demonstrating that one could ditch the old minor-major harmonies in favor of slinky, Oriental-sounding chromatic harmonies.

Liszt eventually went further than anyone else (listen to his Bagatelle sans tonalité, below), just as he concertized further east than anyone else, well into Asia.

As the 20th Century arrived, modern composers sought to reduce music to a fundamental particle, in imitation of what the physicists were doing with matter. Thus, they sought to split traditional harmonies like so many hydrogen atoms. Tonality broke down completely, which in the late 1960’s was what caused the avant-garde Estonian composer Arvo Pärt to break down completely. And what led him out of his breakdown, as we shall see, was the modal music of the 12th Century.

The impact of Liszt’s chromatic explorations is an open book. Liszt’s works seeded the Wagnerians, the Impressionists, even the Second Viennese School (Schönberg, Berg, Webern). Which second-generation trends are appearing in the wake of Pärt’s radical re-purposing of the diatonic scale? I will have a thought-provoking conjecture about this in the summation of this article.

Franz Liszt and his Mid-Life Crisis

As noted above, both Pärt and Liszt had gone through periods in mid-life of artistic breakdown and profound soul-searching. Both emerged with a vision of a simplified musical language. Both wrestled with every artist’s Leviathan, Too Much Freedom. Both were internally influenced by their relationships to Big Religion. And aesthetically their paths crossed at the intersection of Depression and Circumspection.

Liszt and Pärt are very different people with mostly different life experiences. Both internalized and then externalized their private losses (for Pärt, the constant pressure to conform from the mediocrities at the Composer’s Union in Moscow; and exile from his homeland, Estonia, for he and his family; for Liszt, the Pope’s denial of a marriage annulment for Princess Caroline Sayn-Wittgenstein, his mistress and intellectual muse; and the deaths of two grown children and, later, his great friend, Wagner). But Liszt was living in public, and Pärt was mostly hidden for the first half of their lives. (Of course, Pärt is still very much alive at the age of 79.)

Sacheverell Sitwell, in Liszt (1977), contrasts Chopin’s many ballades, polonaises and sonatas with those Liszt wrote in the years following Chopin’s death (in 1849), believed by some to be a memorial to his Polish colleague, as private expression versus public expression. I have thought about this observation many times. Sitwell puts into words a gnawing sensation that many music people have felt about Liszt’s music: that Romanticism is all about finding a voice for one’s inner world, and Liszt’s compositions, which are about force majeur and overwhelming physical display, enfolds a kind of white noise that distorts that inner voice.

But this is true only until Liszt starts experiencing his reversals, a few years before he quits his post as Kapellmeister in Weimar, which he had held for nineteen years (1842-1861). He had been repeatedly rebuffed by the critics for his “Music of the Future”.

Liszt retired from the prestigious Weimar post and moved to the spartan Convento della Madonna del Rosario near Vatican City while he took minor Franciscan orders, becoming known as the Abbé Liszt in 1867.

His musical style changed radically. It became inward-looking, suggesting a very personal interpretation of Catholicism. Bravura and virtuosity were stripped from his aesthetic like old paint. In their place he substituted directness. Instead of creating music that conveyed the all-consuming power of Nature, he composed music of pain and survival, of gentleness as a lesson of fear. His students and colleagues sought to hide these works from the public, believing that the music would destroy Liszt’s reputation.

Liszt was of course thoroughly conversant in the harmonic potential of the chromatic scale. He had composed music throughout his career as a touring virtuoso and in Weimar exploring the sudden emotional changes that chromatic harmonies and chromatic harmonic modulations elicited. Like many a Romantic, he reveled in the aesthetic of the strange, and his chromatic passages made his audiences’ neck-hairs stand up. He combined this chromaticism with the blinding velocity and oceanic sonorities of his piano-playing. No wonder countesses swooned and gentlemen fought to get a view of his hands.

But the onset of depression bled the athletic vitality out of his Muse. Instead of relying on displays of bravura created to evoke frenzy, he reverted to his only true friends, the twelve chromatic scale tones. Not that he abandoned the extramusical references, implicit and explicit, that were the signature of his Romanticism.

It’s more like this: Liszt had a form of synesthesia called chromesthesia or sound > color synesthesia. V. S. Ramachandran notes in The Telltale Brain that one of the orchestra musicians in Weimar reported that Liszt had asked the orchestra to play a passage “less blue, more purple”. Liszt, it appears, saw specific colors when he heard certain tones.

Before his depression, his High Romanticism was, in his mind, perhaps, a succession of flash-mobs of colors and sound. In his depression, the crowds were dispersed, and he was left to confront the tones alone, one-on-one. An augmented chord was not just a leitmotov or theme; it assumed complex layers of meaning. It had a personality, a moral presence.

Liszt built his late music on squibs and dashes of music: Middle Eastern scales (Hungary was for centuries the western frontier of the Ottoman Empire), unresolved melodic phrases (many of his late compositions just die away, as though abandoned during a lapse of senescence), whole-tone harmonies (what playing every other key on the keyboard sounds like, a language embraced in the Belle Époque by Debussy). He wrote titles like Resignazione (Resignation), Schlaflos! Frage und Antwort (Sleepless! Question and Answer), Die Trauergondel – La Lugubre Gondola (The Gondola of Sadness), Am Grabe Richard Wagners (At Richard Wagner’s Grave), Nuages Gris (Gray Clouds). You get the picture.

Links to various late Liszt works on YouTube

I have chosen to provide Internet links to various of Liszt’s late compositions that convey their melancholy and world-weariness, as well as the prevailing spartan musical language and timbres.

19th Hungarian Rhapsody http://youtu.be/zUeEJn2aezk

Am Grabe Richard Wagners (At Richard Wagner’s Grave) http://youtu.be/hpG_jzFb-Zc

Bagatelle sans tonalite http://youtu.be/cwS4kyGl1nE

Csardas Macabre http://youtu.be/sHlkVrdBKR8

Élégie No. 1 http://youtu.be/zua086ji7Jc

Élégie No. 2 http://youtu.be/AvGT02Hy6rQ

Jadis (Ehemals, The Good Old Days) from Christmas Tree, http://youtu.be/fvlDVze_yE4

La Lugubre Gondola No. 1 (The Gondola of Sadness) http://youtu.be/U0sRuLKgnuM

La Lugubre Gondola No.2 http://youtu.be/FfMzihgKi-A

Nuages Gris (Gray Clouds) http://youtu.be/wkWgszQlSEU

Resignazione (Resignation) http://youtu.be/d4l4F0yVk4I

Richard Wagner – Venedig http://youtu.be/FU0O_fjsyag

Schlaflos! Frage und Antwort http://youtu.be/Kyo_KGYWMKs

Unstern http://youtu.be/WsAsSOtXFhY

Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe (From the Cradle to the Grave), symphonic poem, http://youtu.be/gXzqOfc_LNw

* * *

His language had become epigrammatic,

every gesture a stab in the heart.

Which brings us to our Estonian contemporary,

Arvo Pärt.

* * *

(Tune in tomorrow for part two of this series…)

BIO: Contributor Allan Greene has been a dancers’ musician for nearly forty years. He is a composer, pianist, teacher, conductor, music director, father to Oliver, 9, and Ravi, 6, and husband to Juliana Boehm. He has also been an architect, an editor, a writer and a boiler mechanic. He lives and works in New York City. His ballet class music can be found on www.BalletClassTunes.com